Andrey white why. Andrey white

Like many other contemporary Russian writers, Andrei Bely became famous under a pseudonym. His real name is Boris Nikolaevich Bugaev. [Cm. also an article by Andrei Bely - life and works.] He was born in Moscow in 1880 - in the same year as Blok. His father, Professor Bugaev (Professor Letaev in the writings of his son), was an outstanding mathematician, correspondent of Weierstrass and Poincare, dean of the faculty of Moscow University. The son inherited from him an interest in the most difficult to understand mathematical problems.

He studied at the private gymnasium of L. I. Polivanov, one of the best teachers in Russia of that time, which inspired him with a deep interest in Russian poets. In his youth, Bely met with the great philosopher Vladimir Solovyov and early became an expert on his mystical teachings. Bely became close to Solovyov’s nephew, poet Sergei. Both of them were imbued with an ecstatic expectation of an apocalypse, quite realistically and specifically believed that the first years of the new, XXth, century would bring a new revelation - the revelation of the Feminine Hypostasis, Sofia, and that her coming would completely change and transform life. These expectations were further strengthened when friends learned about Blok's visions and poetry.

Russian poets of the twentieth century. Andrey Bely

At this time, Andrei Bely studied at Moscow University, which took him eight years: he received a diploma in philosophy and mathematics. Despite his brilliant abilities, the professor looked askance at him because of his "decadent" writings - some did not even give him a hand at his father's funeral. The first of the “decadent” scriptures (prosaic) appeared in 1902 under the annoying name Symphony (Second dramatic) Several extremely subtle critics (M. S. Solovyov — Sergei’s father, Bryusov and Merezhkovsky with Gippius) immediately recognized something completely new and promising here. This almost mature work gives a complete picture of both Bely’s humor and his amazing gift of writing musically organized prose. But critics reacted to this “symphony” and to what followed, with indignation and anger, and for several years Bely replaced Bryusov (whom they began to recognize) as the main target of attacks on “decadents”. He was called an obscene clown, whose tricks desecrate the sacred field of literature. The attitude of criticism is understandable: almost all Bely’s works undoubtedly have an element of tomfoolery. Per Second symphonyfollowed First (Northern, heroic, 1904), Third (Return, 1905) and Fourth (Blizzard cup, 1908), as well as a collection of poems Gold in Azure (1904) - and everyone met the same reception.

In 1905, Bely (like most Symbolists) was captured by the wave the revolutionwhich he tried to combine with Solovyov's mysticism. But the degeneration of the revolution into criminal anarchy caused Bely depression, as well as Blok, and he lost faith in his mystical ideals. Suppression poured out in two poetry collections that appeared in 1909: realistic - Asheswhere he picks up the Nekrasov tradition, and Urnwhere he talks about his wanderings in the abstract desert neo-Kantian metaphysics. But Bely’s despair is deprived of Blok’s gloomy and tragic bitterness, and the reader unwillingly takes him not so seriously, all the more so since Bely himself constantly distracts him with his humorous cockbets.

All this time, Bely wrote prose volume after volume: he wrote brilliant but fantastic and impressionistic critical articles in which he explained writers from the point of view of his mystical symbolism; wrote expositions of his metaphysical theories. The Symbolists appreciated him highly, but he was hardly known to the general public. In 1909, he published his first novel - Silver dove . This wonderful work, which was soon to have a huge impact on Russian prose, at first went almost unnoticed. In 1910, Bely read a series of reports at the Petersburg "Poetry Academy" about Russian prosody - a date from which the very existence of Russian prosody as a branch of science can be counted.

In 1911, he married a girl who bore the poetic name Asya Turgenev and was indeed a relative of the famous writer. The following year, a young couple met the famous German "anthroposophist" Rudolf Steiner. The Steiner “anthroposophy” is a crudely concretized and detailed treatment of the symbolist worldview, which considers the human microcosm parallel in all details to the universal macrocosm. Bely and his wife were fascinated by Steiner and spent four years in his magical establishment in Dornach, near Basel (the Goetheanum). They took part in the construction of Johanneum, which was to be built only by Steiner adepts, without the intervention of the unenlightened, i.e. professional builders. During this time, Bely published his second novel Petersburg (1913) and wrote Kotika Letaeva, which was published in 1917. When broke out World War IHe took a pacifist position. In 1916 he had to return to Russia for military service. But the revolution saved him from sending him to the front. Like Block, he was influenced Ivanov-Razumnik and his scythian"Revolutionary messianism. Bolsheviks Bely welcomed as a liberation and destructive storm, which will deal with the decrepit "humanistic" European civilization. In his (very weak) poem Christ is risen (1918) he, even more persistently than Blok, identifies Bolshevism with Christianity.

Like Blok, Bely very soon lost faith in this identity, but, unlike Blok, did not fall into a dull prostration. On the contrary, it was precisely in the worst years of Bolshevism (1918–1921) that he developed a storm of activity, inspired by faith in the great mystical revival of Russia, growing in spite of the Bolsheviks. It seemed to him that in Russia before his eyes a new “culture of eternity” was emerging that would replace the humanistic civilization of Europe. And indeed, in these terrible years of famine, deprivation and terror in Russia there was an amazing flowering of mystical and spiritualistic creativity. White has become the center of this fermentation. He founded Volfilu (Free Philosophical Association), where the most burning problems of mystical metaphysics in their practical aspect were freely, sincerely and originally discussed. He published Dreamer's Notes (1919–1922), a non-periodical journal, a mixture that contains almost all the best that was published during these difficult two years. He taught versification to proletarian poets and lectured almost every day with incredible energy.

During this period, in addition to many small works, he wrote Crank notes, Crime of Nikolay Letaev (continued Kotika Letaeva), a big poem First date and Memories of the Block. Together with Blok and Gorky (who did not write anything then and therefore did not count), he was the largest figure in Russian literature - and much more influential than those two. When the book trade revived (1922), the publishers first began to print Bely. In the same year he left for Berlin, where he became the same center among emigrant writers as he was in Russia. But his ecstatic, restless spirit did not allow him to stay abroad. In 1923, Andrei Bely returned to Russia, because only there he felt contact with the messianic revival of Russian culture, eagerly awaited by him.

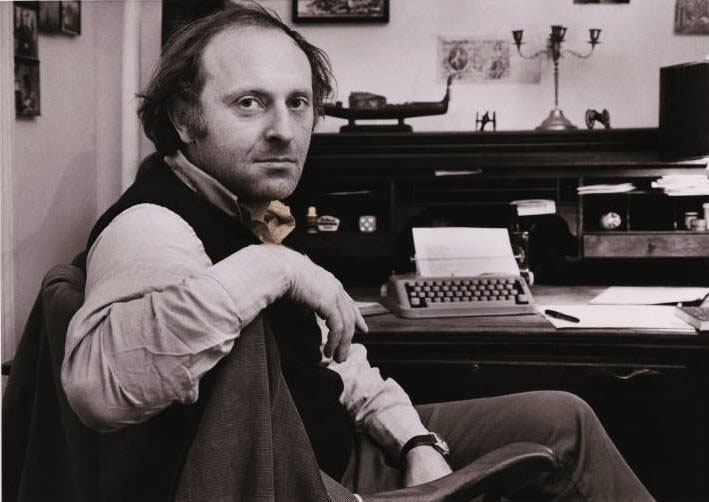

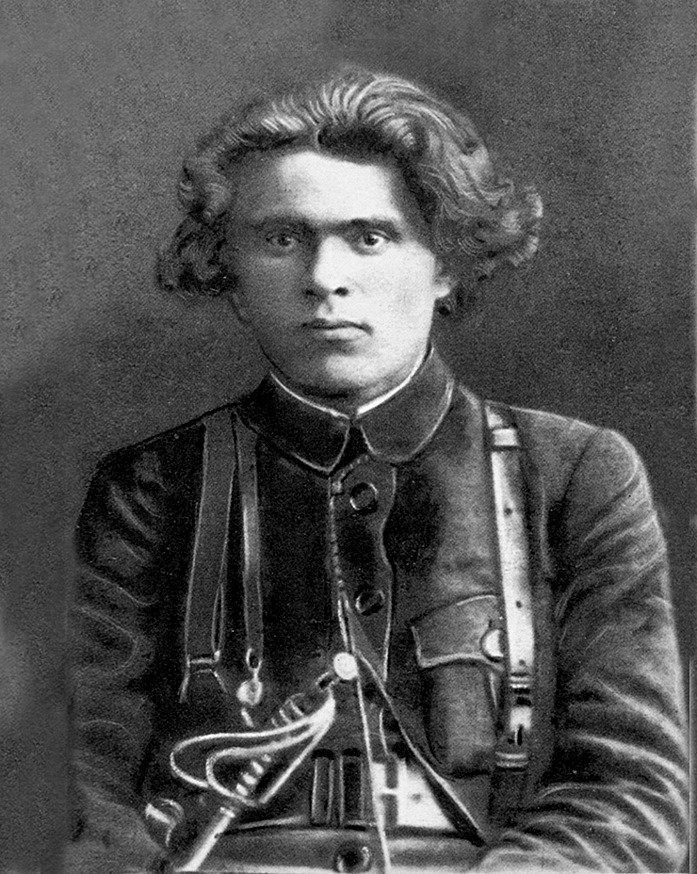

Portrait of Andrei Bely. Artist K. Petrov-Vodkin, 1932

However, all his attempts to establish lively contact with Soviet culture were hopeless. Communist ideologists Andrei Bely did not recognize. Even in Berlin, he broke with Asya Turgeneva, and upon returning to the USSR, cohabited with Anna Vasilyeva, whom she officially married in 1931. She has a writer in her arms and died on January 8, 1934 in Moscow after several strokes.

(1880 - 1934)White Andrey is a pseudonym. Real name - Bugaev Boris Nikolaevich, poet.

Born on October 14 (26 n.a.s.) in Moscow in the family of a professor at Moscow University. Received a wonderful home education. He studied at the gymnasium of the large teacher L. Polivanov, where his outstanding humanitarian talents manifested themselves in the studies of literature and philosophy. Among the Russian classics, N. Gogol and F. Dostoevsky particularly appreciated. In 1903 he graduated from the Natural Department of the Faculty of Mathematics of Moscow University. Along with the study of the works of C. Darwin and the positivist philosophers, he was fond of Theosophy and Occultism, religious philosophy and poetry of Vl. Solovyov and philosophical and poetic creativity F. Nietzsche. At the same time, he "took religious matters seriously."

Belonged to the symbolists of the "younger generation" (together with A. Blok, Vyach. Ivanov, S. Soloviev, Ellis). In 1904, the first collection of poems, "Gold in Azure," was published, supplemented by a special section, "Lyrical passages in prose." A. Bely was one of the theorists of Russian symbolism of the "second wave", the developer of a new aesthetic worldview. Developing the thesis about music as the dominant form of art and the need to subordinate others to it, he tried to create a literary work according to musical laws: these are his four "symphonies" - "Severnaya" (1901), "Dramatic", "Return" (1902), " Snowstorm Cup "(1907), embodying the basic ideas of Russian religious-philosophical, theurgical symbolism. From "symphonies" a direct line begins to the ornamental style of Bely's first novel, "Silver Pigeon," written a year later.

The revolution of 1905–07 forced A. Bely to turn to reality, aroused interest in social problems. In 1909, the collections of Ashes, then The Urn, were published.

In 1912, together with his wife, artist A. Turgeneva, he left for Europe, where he was fond of the mystical teachings of R. Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy. In 1914 he settled in the anthroposophical center in Switzerland, together with other followers of Steiner, took part in the construction of St. John’s Church. Here he finds war, and only in 1916 he returned to Russia.

In these years, prose works occupy a major place in his work. Among them, the most famous novel is Petersburg (1913 - 14, second edition - 1922). A. Bely was not hostile to the October Revolution, although he did not become its singer. In the post-revolutionary years he taught classes on the theory of poetry with young writers in Proletkult, and published the journal Notes of Dreamers.

In the 1920s, the novels Kotik Letaev (1922), The Baptized Chinese (1927), and the historical epic Moscow were written.

A. Bely devoted the last years of his life to writing extensive memoirs of extremely great interest for history and literary criticism ("At the Turn of the Century", 1930, "Beginning of the Century. Memoirs", 1933, "Between Two Revolutions", 1934). January 8, 1934 he died in Moscow.

Andrey Bely (real name Boris Nikolayevich Bugaev; October 14 (26), 1880, Moscow, Russian Empire - January 8, 1934, Moscow, RSFSR, USSR) - Russian writer, poet, critic, poet ; one of the leading figures of Russiansymbolism.

Born in the family of professor Nikolai Vasilyevich Bugaev, a famous mathematician and philosopher, and his wife Alexandra Dmitrievna, nee Egorova. Until twenty-six years he lived in the very center of Moscow, on the Arbat; In the apartment where he spent his childhood and youth, a memorial apartment is currently operating. In the years 1891-1899. He studied at the famous gymnasium of L.I. Polivanov, where in the last classes he became interested in Buddhism, occultism, while studying literature. A special influence on Boris was then exerted by Dostoevsky, Ibsen, Nietzsche. In 1895, he became close friends with Sergei Solovyov and his parents - Mikhail Sergeyevich and Olga Mikhailovna, and soon with Mikhail Sergeyevich’s brother - the philosopher Vladimir Solovyov.

In 1899 he entered the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics of Moscow University (Natural Division). In his student years he became acquainted with the "senior symbolists." From his youth, he tried to combine artistic and mystical moods with positivism, with a desire for exact sciences. At university, he works on the zoology of invertebrates, studies Darwin, chemistry, but does not miss a single issue of the World of Art.

In the fall of 1903, a literary circle was organized around Andrei Bely, called the Argonauts.

Our circle did not have a common, stamped worldview, there were no dogmas: from now until now they have been united in quests, not in achievements, and therefore many among us found ourselves in the crisis of yesterday and in the crisis of worldview that seemed outdated; we welcomed him in attempts to give birth to new thoughts and new attitudes, ”Andrei Bely recalled.

In 1904, the Argonauts gathered in an apartment nearAstrova . At one of the meetings of the circle, it was proposed to publish a literary and philosophical collection entitled “Free conscience”, and in 1906 two books of this collection were published.

In 1903, Bely entered into correspondence with A.A. Blok, in 1904 a personal acquaintance took place. Prior to this, in 1903 he graduated with honors from the University, but in the fall of 1904 he entered the Faculty of History and Philology of the University, choosing B.A. Fokht as the leader; however, in 1905 he stopped attending classes, in 1906 he filed a petition for expulsion and began to collaborate in Libra (1904-1909).

Bely lived for more than two years abroad, where he created two collections of poems that were dedicated to Blok and Mendeleev. Returning to Russia, in April 1909, the poet became close to Asya Turgeneva (1890-1966) and, together with her, in 1911 made several trips through Sicily - Tunisia - Egypt - Palestine (described in Travel Notes). In 1912, in Berlin, he met Rudolf Steiner, became his student and, without looking back, surrendered to his apprenticeship and anthroposophy. In fact, moving away from the previous circle of writers, he worked on prose works. When the war of 1914 broke out, Steiner and his students, including Andrei Bely, moved to Dorny, Switzerland. There began the construction of the Ivanovo building - the Goetheanum. This temple was built with the hands of students and followers of Steiner. March 23, 1914 in the Swiss city of Bern, a civil marriage was concluded between Anna Alekseevna Turgeneva and Boris Nikolaevich Bugaev. In 1916, B.N. Bugaev was called up for military service and arrived in Russia in a roundabout way through France, England, Norway and Sweden. Asya did not follow him.

After the October Revolution, he taught classes on the theory of poetry and prose in the Moscow Proletcult among young proletarian writers. Since the end of 1919, Bely was thinking about going abroad in order to return to his wife in Dorn. But they released him only at the beginning of September 1921. He met with Asya, who invited him to disperse forever. According to the verses of that time, according to his behavior (“Christopherly's White”, as Marina Tsvetaeva puts it), you can feel that he was very hard at this parting.

Asya decided to leave her husband forever and stayed in Dornach, devoting herself to serving the cause of Rudolf Steiner. She was called the "anthroposophical nun." Being a talented artist, Asya managed to maintain a special style of illustrations, which replenished all anthroposophical publications. Her “Memories of Andrei Bely”, “Memories of Rudolf Steiner and the construction of the first Goetheanum” reveal to us the details of their acquaintance with anthroposophy, Rudolf Steiner and many famous talented people of the Silver Age. White was left completely alone. He devoted a large number of verses to Asa. Her image can be recognized in Katya from the Silver Dove.

In October 1923, Bely returned to Moscow; Asya is forever in the past. But a woman appeared in his life who was destined to spend the last years with him. Claudia Nikolaevna Vasilieva (nee Alekseeva; 1886-1970) became Bely's last girlfriend, to whom he did not feel love, but held on to her, as if for a savior. Quiet, obedient, caring Claude, as the writer called her, became July 18, 1931 the wife of Bely. Prior to that, from March 1925 to April 1931 they rented two rooms inKuchine near Moscow. The writer died in her arms from a stroke, which became a consequencesunstroke January 8, 1934 in Moscow. Lyubov Dmitrievna Mendeleev survived her former lover for five years.

Literary debut - “Symphony (2nd, dramatic)” (M., 1902). It was followed by the “Northern Symphony (1st, heroic)” (1904), “Return” (1905), “Snowstorm Cup” (1908) in the individual genre of lyrical rhythmic prose with characteristic mystical motifs and a grotesque perception of reality. Entering the circle of Symbolists, he participated in the magazines World of Art, The New Way, Libra, The Golden Fleece, and Pass. An early collection of poems “Gold in Azure” (1904) is characterized by formal experimentation and characteristic symbolist motifs. After returning from abroad, he published collections of poems “Ashes” (1909; the tragedy of rural Rus), “Urn” (1909), the novel “Silver Dove” (1909; ed. 1910), essays “The Tragedy of Creativity. Dostoevsky and Tolstoy ”(1911).

The results of his own literary and critical activity, partly symbolism in general, are summarized in collections of articles “Symbolism” (1910; includes poetry), “Green Meadow” (1910; includes critical and polemical articles, essays on Russian and foreign writers), “ Arabesques ”(1911). In 1914–1915 the first edition of the novel Petersburg was published, which is the second part of the East or West trilogy. In the novel "Petersburg" (1913-1914; revised abridged version of 1922), a symbolized and satirical image of Russian statehood. The first in a series of autobiographical novels conceived - "Kotik Letaev" (1914-1915, ed. 1922); the series is continued by the novel “The Baptized Chinese” (1921; ed. 1927). In 1915 he wrote the study "Rudolf Steiner and Goethe in the worldview of our time" (M., 1917)

Understanding the First World War as a manifestation of the general crisis of Western civilization is reflected in the cycle “On the Pass” (“I. The crisis of life”, 1918; “II. The crisis of thought”, 1918; “III. The crisis of culture”, 1918). The perception of the life-giving element of the revolution as a saving way out of this crisis is in the essay “Revolution and Culture” (1917), the poem “Christ Has Risen” (1918), and the collection of poems “The Star” (1922). Also in 1922 in Berlin he published the “sound poem” “Glossolalia”, where, based on the teachings of R. Steiner and the method of comparative historical linguistics, he developed the theme of creating a universe from sounds. Upon returning to Soviet Russia (1923), he creates the novel “Moscow” (“Moscow Eccentric”, “Moscow under attack”; 1926), the novel “Masks” (“1932”), writes his memoirs, “Memories of the Block” (1922— 1923) and the memoir trilogy “At the Turn of Two Centuries” (1930), “The Beginning of the Century” (1933), “Between Two Revolutions” (1934), theoretical and literary studies “Rhythm as a Dialectic and The Bronze Horseman” (1929) and Gogol’s Mastery (1934).

Novels

- "" Silver dove. The story in 7 chapters ”(Moscow: Scorpio, 1910; circulation of 1000 copies); ed. Pashukanisa, 1917; ed. The Age, 1922

- “Petersburg” (in the 1st and 2nd collections of “Sirin” (St. Petersburg, 1913; circulation - 8100 copies each), ending in the 3rd collection of “Sirin” (St. Petersburg, 1914; circulation of 8100 copies .; separate edition ([PG.], 1916; circulation of 6000 copies); revised version in 1922 - parts 1, 2. M: Nikitinsky Subbotniks, 1928; circulation of 5000 copies); Berlin, Epoch, 1923

- "The Cat of Letaev" (1915; ed. - St. Petersburg: Epoch, 1922; circulation of 5000 copies.).)

- “Baptized Chinese” (as “The Crime of Nikolai Letaev” in the 4th edition of the alm. “Notes of Dreamers” (1921); Department of Publishing, Moscow: Nikitinsky Subbotniks, 1927; circulation of 5000 copies)

- Moscow Eccentric (Moscow: Krug, 1926; circulation of 4,000 copies), also 2nd ed. - M.: Nikitinsky Subbotniks, 1927

- “Moscow under attack” (Moscow: Krug, 1926; circulation of 4,000 copies), also 2nd ed. - M.: Nikitinsky Subbotniks, 1927

- “Masks. Roman "(M .; L .: GIHL; 1932; circulation of 5000 copies), were published in January 1933

Poetry

- “Gold in Azure” (Moscow: Scorpio, 1904), a collection of poems

- “Ashes. Verses” (St. Petersburg: Rosehip, 1909; circulation of 1000 copies; edition 2, period. - M.: Nikitinsky Subbotniks, 1929; circulation of 3000 copies)

- "Urn. Poems ”(Moscow: Grif, 1909; circulation of 1200 copies)

- "Christ is risen. Poem ”(St. Petersburg: Alkonost, 1918; circulation of 3000 copies), published in April 1919

- “First date. Poem "(1918; publ. Ed. - St. Petersburg: Alkonost, 1921; circulation of 3000 copies; Berlin, Slovo, 1922)

- "Star. New Poems ”(Moscow: Alcyone, 1919; P., GIZ, 1922)

- “The Queen and the Knights. Tales ”(St. Petersburg: Alkonost, 1919)

- "Star. New Poems ”(St. Petersburg: State Publishing House, 1922; circulation of 5000 copies).

- After Separation, Berlin, The Age, 1922

- “Glossolalia. The Poem of Sound ”(Berlin: Age, 1922)

- “Poems about Russia” (Berlin: The Age, 1922)

- Poems (Berlin, ed. Grzhebina, 1923)

Documentary prose

- Traveling Notes (2 volumes) (1911)

- “Ofeira. Travel notes, part 1. " (M .: Book publishing of writers in Moscow, 1921; circulation of 3,000 copies.)

- “Travel notes, vol. 1. Sicily and Tunisia” (Moscow; Berlin: Helikon, 1922)

- “Memories of the Bloc” (Epic. Literary monthly under the editorship of A. Bely. M .; Berlin: Helikon. No. 1 - April, No. 2 - September, No. 3 - December; No. 4 - June1923)

- “At the Turn of Two Centuries” (M .; L .: Land and Factory, 1930; circulation of 5000 copies.)

- “The Beginning of the Century” (M .; L .: GIHL, 1933; circulation of 5,000 copies).

- “Between Two Revolutions” (L., 1935)

Articles

- "Symbolism. Book of Articles ”(Moscow: Musaget, 1910; circulation of 1000 copies)

- “The meadow is green. Book of Articles ”(Moscow: Alcyone, 1910; circulation of 1200 copies)

- “Arabesques. Book of Articles ”(Moscow: Musaget, 1911; circulation of 1000 copies)

- "The tragedy of creativity." M., Musaget, 1911

- "Rudolf Steiner and Goethe in the worldview of our time" (1915)

- “Revolution and Culture” (Moscow: Publishing House of G. A Leman and S. I. Sakharov, 1917), brochure

- “Rhythm and Meaning” (1917)

- “On the rhythmic gesture” (1917)

- “On the pass. I. The crisis of life ”(St. Petersburg: Alkonost, 1918)

- “On the pass. II. The crisis of thought ”(St. Petersburg: Alkonost, 1918), released in January 1919

- “On the pass. III. The crisis of culture ”(St. Petersburg: Alkonost, 1920)

- "Sirin of the learned barbarism." Berlin, The Scythians, 1922

- “On the Meaning of Knowledge” (St. Petersburg: Epoch, 1922; circulation of 3000 copies)

- “The poetry of the word” (St. Petersburg: Epoch, 1922; circulation of 3000 copies)

- “Wind from the Caucasus. Impressions ”(Moscow: Federation, Krug, 1928; circulation of 4000 copies).

- “Rhythm as a dialectic and The Bronze Horseman.” Research ”(Moscow: Federation, 1929; circulation of 3000 copies)

- “Gogol’s skill. The Study ”(M.-L.: GIHL, 1934; circulation of 5000 copies), published posthumously in April 1934

miscellanea

- “The tragedy of creativity. Dostoevsky and Tolstoy ”(Moscow: Musaget, 1911; circulation of 1000 copies), brochure

- Symphonies

- Northern Symphony (heroic) (1900; published - M .: Scorpio, 1904)

- Symphony (dramatic) (Moscow: Scorpio, 1902)

- Return. III Symphony (Moscow: Grif, 1905. Berlin, "Sparks", 1922)

- Cup of blizzards. The Fourth Symphony ”(Moscow: Scorpio, 1908; circulation of 1000 copies).

- “One of the cloisters of the kingdom of shadows” (L .: State Publishing House, 1924; circulation of 5000 copies), essay

Editions

- Andrey Bely Petersburg - Printing house of M.M. Stasyulevich, 1916.

- Andrey Bely On the pass. - Alkonost, 1918.

- Andrey Bely One of the cloisters of the kingdom of shadows. - L.: Leningrad Gublit, 1925.

- Andrey Bely Petersburg - M.: “Fiction, 1978.

- Andrey Bely Selected Prose. - M.: Sov. Russia, 1988. -

- Andrey Bely Moscow / Comp., Entry. Art. and note. S.I. Timina. - M.: Sov. Russia, 1990 .-- 768 p. - 300,000 copies.

- Andrey Bely Baptized Chinese. - "Panorama", 1988. -

- White A. Symbolism as a worldview. - M.: Republic, 1994 .-- 528 p.

- Andrey Bely Collected Works in 6 volumes. - M.: Terra - Book Club, 2003-2005.

- Andrey Bely Gogol's skill. Study. - Book Club of Bookies, 2011. -

- White A. Poems and poems / Intro. article and comp. T. Yu. Khmelnitsky; Prep. text and note. N. B. Bank and N. G. Zakharenko. - 2nd edition. - M., L .: Sov. writer, 1966. - 656 p. - (The poet's library. A large series.). - 25,000 copies.

- White A. Petersburg / Edition prepared by L.K. Dolgopolov; Repl. ed. Acad. D.S. Likhachev. - M.: Nauka, 1981 .-- 696 p. - (Literary monuments).

Andrei Bely a short biography is set out in this article.

Andrey Bely short biography

Andrey Bely (real name Boris Nikolaevich Bugaev- Russian writer; one of the leading figures of Russian symbolism and modernism in general.

Born October 14, 1880 in Moscow in the family of a scientist, mathematician and philosopher Nikolai Bugaev.

In the years 1891-1899. graduated from the famous Moscow gymnasium of L. I. Polivanov, he developed an interest in poetry.

In 1899, at the insistence of his father, he entered the natural department of the Physics and Mathematics Faculty of Moscow University. Which he graduated with honors in 1903.

In 1902, Andrei Bely, together with friends, organized the Argonauts literary circle. And after 4 years, the members of the circle published two collections of “Free Conscience”.

In 1903, Bely began correspondence with Alexander Blok, and a year later their personal acquaintance took place.

In 1904, Andrei Bely's first poetry collection, Gold in Azure, was published.

In the fall, he re-entered the Moscow University of History and Philology, but in 1905 he stopped attending lectures, and in 1906 he filed a petition for expulsion in connection with a trip abroad.

Two years later, Bely returned to Russia. And then he married Asa Turgeneva. He traveled a lot until one day he met Rudolf Steiner and became his student.

In 1909 he became one of the co-founders of the Musaget Publishing House. Since 1912, he edited the journal "Proceedings and Days."

In 1916, Andrei Bely returned to Russia, but alone, without a wife.

Since the end of 1919, Bely thought about returning to his wife in the Dorn, he was released abroad only in 1921. In 1921-1923 he lived in Berlin, where he was breaking up with Turgeneva,

In October 1923, Bely unexpectedly returned to Moscow for his girlfriend Claudia Vasilyeva. In March 1925, he rented two rooms in Kuchin near Moscow. The writer died in the arms of his wife Claudia Nikolaevna on January 8, 1934 from a stroke - a consequence of a sunstroke that happened to him in Koktebel.

poetry; one of the leading figures of Russian symbolism and modernism in general.

Biography

In 1899, at the insistence of his father, he entered the natural department of the Physics and Mathematics Faculty of Moscow University. From his youth, he tried to combine artistic and mystical moods with positivism, with a desire for exact sciences. At university, he works on the zoology of invertebrates, studies the works of Darwin, chemistry, but does not miss a single issue of the World of Art. In the fall of 1899, Boris, as he put it, “completely devotes himself to the phrase, the syllable”.

In December 1901, Bely met the “senior Symbolists” - Bryusov, Merezhkovsky and Gippius. In the fall of 1903, a literary circle was organized around Andrei Bely, called the Argonauts. In 1904, the "Argonauts" gathered at Astrov’s apartment. At one of the meetings of the circle, it was proposed to publish a literary and philosophical collection entitled “Free conscience”, and in 1906 two books of this collection were published.

In 1903, Bely entered into correspondence with Alexander Blok, and a year later their personal acquaintance took place. Prior to this, in 1903 he graduated with honors from the university. Since the founding of the Libra magazine in January 1904, Andrei Bely began to work closely with him. In the fall of 1904, he entered the Faculty of History and Philology of Moscow University, choosing B. A. Voht as the leader; however, in 1905 he stopped attending classes, in 1906 he filed a petition for expulsion and began to engage exclusively in literary work.

After a painful break with Blok and his wife Lyubov Mendeleeva, Bely lived for six months abroad. In 1909 he became one of the co-founders of the Musaget Publishing House. In 1911 he made a number of trips through Sicily - Tunisia - Egypt - Palestine (described in the Travel Notes). In 1910, Bugaev, relying on his knowledge of mathematical methods, gave lectures on prosody to beginner poets, according to D. Mirsky, "the date from which the very existence of Russian poetry as a branch of science can be counted off."

Since 1912 he edited the journal "Works and Days", the main theme of which was the theoretical issues of the aesthetics of symbolism. In 1912, in Berlin, he met Rudolf Steiner, became his student and, without looking back, surrendered to his apprenticeship and anthroposophy. In fact, moving away from the previous circle of writers, he worked on prose works. When the war of 1914 broke out, Steiner with his students, including Andrei Bely, were in the Swiss Dornach, where the construction of the Goetheanum began. This temple was built with the hands of students and followers of Steiner. Before the start of World War I, A. Bely visited the grave of Friedrich Nietzsche in the village of Röcken near Leipzig and Cape Arkona on the island of Rügen.

In 1916, B.N. Bugaev was called to Russia "to test his attitude to military service" and arrived in Russia in a roundabout way through France, England, Norway and Sweden. The wife did not follow him. After the October Revolution, he taught classes on the theory of poetry and prose in the Moscow Proletcult among young proletarian writers.

Since the end of 1919, Bely thought about returning to his wife in Dorny, he was released abroad only at the beginning of September 1921. From the explanation with Asya it became clear that the continuation of a family life together was impossible. Vladislav Khodasevich and other memoirists remembered his broken, comradely behavior, the “dancing” of the tragedy in Berlin bars: “his foxtrot is pure whip: not even a whistle, but a christ dance” (Tsvetaeva).

In October 1923, Bely unexpectedly returned to Moscow for his girlfriend Claudia Vasilyeva. “Bely is a dead man, and in no spirit will he be resurrected,” wrote Trotsky, the all-powerful at that time, in Pravda. In March 1925, he rented two rooms in Kuchin near Moscow. The writer died in the arms of his wife Claudia Nikolaevna on January 8, 1934 from a stroke - a consequence of a sunstroke that happened to him in Koktebel. This fate was predicted by him in the collection "Ashes" (1909):

I believed in the golden glitter

He died of sun arrows.

I’ve measured by the thought of the century

But he could not live life.

Personal life

In the years when the Symbolists enjoyed the greatest success, Bely consisted of “love triangles” with two current brothers at once - Valery Bryusov and Alexander Blok. Relations Bely, Bryusov and Nina Petrovsky inspired Bryusov to create the novel "Fiery Angel" (1907). In 1905, Nina Petrovskaya shot at Bely. Triangle White - Block - Lyubov Mendeleev intricately refracted in the novel "Petersburg" (1913). For some time Lyubov Mendeleeva-Blok and Bely met in a rented apartment on Shpalernaya Street. When she informed Bely that she was staying with her husband and wanted to permanently erase him from life, Bely entered a period of deep crisis, which almost ended in suicide. Feeling himself abandoned by all, he went abroad.

Upon his return to Russia in April 1909, Bely became close to Anna Turgeneva (Asya, 1890-1966, niece of the great Russian writer Ivan Turgenev). In December 1910, she accompanied Bely on a trip to North Africa and the Middle East. March 23, 1914 married her. The wedding ceremony took place in Bern. In 1921, when the writer returned to her in Germany after five years in Russia, Anna Alekseevna invited him to leave for good. She remained to live in Dornach, devoting herself to serving the cause of Rudolf Steiner. She was called the "anthroposophical nun." Being a talented artist, Asya managed to develop a special style of illustrations, which replenished anthroposophical publications. Her “Memories of Andrei Bely”, “Memories of Rudolf Steiner and the construction of the first Goetheanum” contain interesting details of their acquaintance with anthroposophy, Rudolf Steiner and many talented people of the Silver Age. Her image can be recognized in Katya from the Silver Dove.

In October 1923, Bely returned to Moscow; Asya is forever in the past. But a woman appeared in his life who was destined to spend the last years with him. Claudia Nikolaevna Vasilieva (nee Alekseeva; 1886-1970) became Bely's last friend. Quiet, caring Claude, as the writer called her, July 18, 1931 became the wife of the White.

Creation

Literary debut - “Symphony (2nd, dramatic)” (M., 1902). It was followed by the “Northern Symphony (1st, heroic)” (1904), “Return” (novel, 1905), “Cup of Snowstorms” (1908) in the individual genre of lyrical rhythmic prose with characteristic mystical motifs and a grotesque perception of reality. Entering the circle of Symbolists, he participated in the magazines World of Art, The New Way, Libra, The Golden Fleece, and Pass.

Literary debut - “Symphony (2nd, dramatic)” (M., 1902). It was followed by the “Northern Symphony (1st, heroic)” (1904), “Return” (novel, 1905), “Cup of Snowstorms” (1908) in the individual genre of lyrical rhythmic prose with characteristic mystical motifs and a grotesque perception of reality. Entering the circle of Symbolists, he participated in the magazines World of Art, The New Way, Libra, The Golden Fleece, and Pass.

An early collection of poems “Gold in Azure” () is distinguished by formal experimentation and characteristic symbolist motifs. After returning from abroad, he published collections of poems “Ashes” (1909; the tragedy of rural Russia), “Urn” (1909), the novel “Silver Pigeon” (1909; Department of Publication 1910), essays “The Tragedy of Creativity. Dostoevsky and Tolstoy ”(1911). The results of his own literary and critical activities, partly symbolism in general, are summarized in collections of articles Symbolism (1910; includes poetry), Green Meadow (1910; includes critical and polemical articles, essays on Russian and foreign writers), " Arabesques ”(1911).

In 1914-1915 the first edition of the novel Petersburg was released, which is the second part of the East or West trilogy. In the novel "Petersburg" (1913-14; revised abridged version of 1922) symbolized and satirical depiction of Russian statehood. The novel is widely recognized as one of the pinnacles of prose of Russian symbolism and modernism in general.

The first in a series of autobiographical novels conceived - "Kotik Letaev" (1914-15, ed. 1922); the series is continued by the novel “The Baptized Chinese” (1921; ed. 1927). In 1915, Bely wrote a study "Rudolf Steiner and Goethe in the worldview of our time" (M., 1917).

Influence

Bely's stylistic style is extremely individualized - it is a rhythmic, patterned prose with numerous fantastic elements. According to V. B. Shklovsky, “Andrei Bely is an interesting writer of our time. All modern Russian prose bears its traces. Pilnyak is the shadow of smoke, if White is smoke. ” To indicate the influence of A. Bely and A. M. Remizov on post-revolutionary literature, the researcher uses the term “ornamental prose”. This direction became the main one in the literature of the first years of Soviet power. In 1922, Osip Mandelstam urged writers to overcome Andrei Bely as “the pinnacle of Russian psychological prose” and to return from weaving words to pure plot action. Beginning in the late 1920s Belov's influence on Soviet literature is steadily fading away.

Addresses in Petersburg

- 01.1905 years - Merezhkovsky’s apartment in the apartment building of A. D. Muruzi - Liteiny prospect, 24;

- 01. - 02.1905 years - furnished rooms "Paris" in the apartment building of P. I. Likhachev - 66 Nevsky Prospect;

- 12.1905 years - furnished rooms "Paris" in the apartment building of P.I. Likhachev - 66 Nevsky Prospect;

- 04. - 08.1906 years - furnished rooms "Paris" in the apartment building of P. I. Likhachev - 66 Nevsky Prospect;

- 01/30. - 03/08/1917 - the apartment of R.V. Ivanov-Razumnik - Tsarskoye Selo, Kolpinskaya street, 20;

- spring 1920 - 10.1921 - apartment building of I. I. Dernov - Slutsky street, 35 (from 1918 to 1944 the so-called Tavricheskaya St.).

see also

Write a review on the article "Andrei Bely"

Notes

- (original in the ImWerden library)

A passage characterizing Andrei Bely

The adjutant looked back at Pierre, as if not knowing what to do with him now.“Don't worry,” Pierre said. “I'll go to the mound, can I?”

- Yes, go, from there everything is visible and not so dangerous. And I'll pick you up.

Pierre went to the battery, and the adjutant rode on. They didn’t see each other anymore, and much after Pierre found out that this adjutant had his arm torn off that day.

The mound Pierre entered was famous (later known to the Russians as the Kurgan battery or Raevsky battery, and the French as la grande redoute, la fatale redoute, la redoute du center [big redoubt, fateful redoubt, central redoubt ] a place around which tens of thousands of people are laid and which the French considered the most important point of position.

This redoubt consisted of a mound on which ditches were dug from three sides. In the dug-in place there were ten firing cannons, stuck out in the shaft aperture.

In line with the mound were guns on both sides, also firing continuously. A little behind the cannons were infantry troops. Entering this mound, Pierre did not think that this place, dug in small ditches, on which several guns stood and fired, was the most important place in the battle.

On the contrary, it seemed to Pierre that this place (precisely because it was located on it) was one of the most insignificant places of the battle.

Entering the mound, Pierre sat down at the end of the ditch surrounding the battery, and with an unconsciously joyful smile looked at what was happening around him. Occasionally Pierre got up with the same smile and, trying not to interfere with the soldiers who were loading and rolling the guns, constantly running past him with bags and charges, walked around the battery. The cannons from this battery fired incessantly one after another, stunning with their sounds and covering the whole neighborhood with powder smoke.

In contrast to the eerieness that was felt between the infantry soldiers of the cover, here, on the battery, where a small number of people engaged in business are white, limited, separated from the others by a ditch, there was felt the same and common to everyone, like a family revival.

The appearance of a non-military figure of Pierre in a white hat at first unpleasantly struck these people. The soldiers, passing by him, looked at his figure in surprise and even frightened. The senior artillery officer, a tall, with long legs, pockmarked man, as if in order to look at the action of the extreme guns, went up to Pierre and looked at him curiously.

A young chubby officer, still a perfect child, obviously, just released from the corps, disposing of two cannons very carefully entrusted to him, strictly turned to Pierre.

“Sir, let me ask you out of the way,” he told him, “you cannot here.”

The soldiers shook their heads disapprovingly, looking at Pierre. But when everyone was convinced that this man in a white hat not only did nothing wrong, but either quietly sat on the slope of the shaft, or with a timid smile, courteously avoiding the soldiers, walked on the battery under the shots as calmly as on the boulevard, then little by little the feeling of unkind bewilderment toward him began to turn into an affectionate and humorous participation, similar to that which soldiers have for their animals: dogs, roosters, goats, and in general animals living with military teams. These soldiers immediately mentally accepted Pierre into their family, appropriated themselves and gave him the nickname. "Our master" was nicknamed him and laughed affectionately about him.

One core blew up the ground a stone's throw from Pierre. He, clearing the earth sprinkled with a core from the dress, looked around with a smile.

- And how are you not afraid, master, right! - the red-necked wide soldier turned to Pierre, grinning strong white teeth.

“Are you afraid?” Asked Pierre.

- But how? - the soldier answered. - After all, she will not have mercy. She sniffs, so guts out. You can't help but be afraid, ”he said, laughing.

Several soldiers with cheerful and affectionate faces stopped beside Pierre. They did not seem to expect him to speak like everyone else, and this discovery pleased them.

- Our business is soldier's. But the master, so amazing. Here so master!

- In places! - shouted a young officer at the soldiers gathered around Pierre. This young officer, apparently, was fulfilling his post for the first or second time, and therefore he treated soldiers and the commander with particular clarity and uniformity.

The erratic firing of guns and rifles intensified throughout the field, especially to the left, where there were Bagration flashes, but because of the smoke of the shots from the place where Pierre was, almost nothing could be seen. Moreover, the observation of how a family (separated from all others) circle of people who were on the battery, absorbed all the attention of Pierre. His first unconsciously joyful excitement, produced by the look and sounds of the battlefield, has now been replaced, especially after the sight of this lonely soldier in the meadow, with a different feeling. Sitting now on the slope of the ditch, he watched the faces surrounding him.

By ten o’clock twenty people had already been taken from the battery; two guns were broken, more and more shells hit the battery and flew, distant bullets, buzzing and whistling. But the people on the battery did not seem to notice this; from all sides there was a cheerful talk and jokes.

- Chinenka! - the soldier shouted at the approaching grenade flying with a whistle. - Not here! To the infantry! - the other added with laughter, noting that the grenade flew over and fell into the ranks of the cover.

- What, friend? - the other soldier laughed at the crouched man under the flying core.

Several soldiers gathered at the rampart, looking at what was happening ahead.

“And they removed the chain, you see, they went back,” they said, pointing through the shaft.

“Look at your own business,” the old non-commissioned officer shouted at them. - They went back, so there is a thing back. - And the non-commissioned officer, taking one of the soldiers by the shoulder, pushed him with his knee. There was laughter.

- Roll to the fifth gun! - shouted from one side.

“At once, in a friendlier way, according to Burlack,” we heard cheerful cries of those who changed the gun.

“Ah, our master almost knocked off his hat,” the red-necked joker laughed at Pierre. “Oh, awkward,” he added reproachfully to the core, which hit the man’s wheel and leg.

- Well you foxes! - the other laughed at the bending militias entering the battery for the wounded.

- Al is not tasty porridge? Ah, the crows, started to sway! - they shouted at the militias, who were hushed up in front of the soldier with his leg torn off.

“That one, small one,” mimicked the men. - They don’t like passion.

Pierre noticed how, after each hit nucleus, after each loss, general revitalization flared up more and more.

Like from an approaching thundercloud, more and more often, lighter and brighter flashes on the faces of all these people (as if in rebuff of the occurring) lightning of a hidden, flaring fire.

Pierre did not look forward at the battlefield and was not interested in knowing what was being done there: he was all absorbed in the contemplation of this, more and more flaring fire, which in the same way (he felt) flared in his soul.

At ten o’clock the infantry soldiers who were ahead of the batteries in the bushes and along the Kamenka River retreated. From the battery you could see how they ran back past her, carrying the wounded on their guns. Some general and his retinue entered the mound and, having talked with the colonel, looked angrily at Pierre, went down again, ordering the infantry cover behind the battery to lie down to be less exposed to shots. Following this, in the ranks of the infantry, to the right of the battery, there was a drum, command screams, and from the battery it was visible how the ranks of the infantry moved forward.

Pierre was looking through the shaft. One face caught his eye. It was an officer who, with a pale young face, walked backwards, carrying a lowered sword, and looked around uneasily.

Rows of infantry soldiers disappeared into the smoke, they heard a long cry and the frequent firing of guns. A few minutes later, crowds of wounded and stretchers passed from there. Shells began to hit the battery even more often. Several people lay uncleared. Around the guns, soldiers moved more troublesome and livelier. No one paid attention to Pierre. Two times they shouted at him angrily because he was on the road. The senior officer, with a frown, with large, quick steps, moved from one gun to another. The young officer, even more reddened, even more diligently commanded the soldiers. The soldiers gave charges, turned, charged and did their job with intense panache. They bounced on the move, like on springs.

A thundercloud moved forward, and that fire burned brightly in all faces, the ignition of which was followed by Pierre. He stood beside the senior officer. A young officer ran up, with his hand to the shako, to the elder.

“I have the honor to report, Mr. Colonel, there are only eight charges, will you order to continue the fire?” - he asked.

- Kartech! - without answering, the senior officer shouted, looking through the shaft.

Suddenly something happened; the officer gasped and, curled up, sat down on the ground, like a shot bird on the fly. Everything became strange, obscure and cloudy in Pierre's eyes.

One after another, the kernels whistled and fought at the parapet, at the soldier, at the cannon. Pierre, who had not heard these sounds before, now only heard these sounds. On the side of the battery, on the right, with a cry of “Hurray,” the soldiers ran not forward, but backward, as Pierre thought.

The nucleus hit the very edge of the shaft, in front of which Pierre stood, poured earth, and a black ball flickered in his eyes, and at the same instant it slammed into something. The militiamen who entered the battery ran back.

- All buckshot! Shouted the officer.

The non-commissioned officer ran to the senior officer and in a frightened whisper (as the butler reports to the master that there is no more wine required) said that there were no more charges.

- Robbers what they do! Cried the officer, turning to Pierre. The face of the senior officer was red and sweaty, his frown glittered. - Run to the reserves, bring the boxes! He shouted, angrily looking around Pierre and turning to his soldier.

“I'll go,” said Pierre. The officer, not answering him, with great strides went to the other side.

- Do not shoot ... Wait! He shouted.

The soldier who was ordered to follow the charges collided with Pierre.

“Oh, gentleman, there is no place for you here,” he said, and ran downstairs. Pierre ran after the soldier, bypassing the place where the young officer sat.

One, another, the third core flew over him, hit in front, from the sides, behind. Pierre ran down. “Where am I?” He suddenly remembered, already running up to the green boxes. He stopped in indecision, to go back or forward. Suddenly a terrible push threw him back to the ground. At the same instant, the brilliance of a large fire illuminated him, and at the same instant there was a deafening thunder, ringing in the ears, crackling and whistling.

Pierre, waking up, was sitting in the back, resting his hands on the ground; the box near which he was was not; only green burnt boards and rags were lying on the scorched grass, and the horse, gritting debris from the debris, galloped away from him, and the other, like Pierre himself, lay on the ground and screeched, piercingly, drawn out.

Pierre, not remembering himself with fear, jumped up and ran back to the battery, as the only refuge from all the horrors that surrounded him.

While Pierre was entering the trench, he noticed that no shots were heard on the battery, but some people were doing something there. Pierre did not have time to understand what kind of people they were. He saw the senior colonel, back to him lying on the shaft, as if looking at something below, and saw one soldier he noticed, who, breaking forward from the people holding his hand, shouted: “Brothers!” - and he saw Something strange.

But he had not yet realized that the colonel had been killed, that the shouting “brothers!” Was a prisoner, that in his eyes another soldier had been bayoneted in the back. As soon as he ran into the trench, a thin, yellow, sweaty-faced man in a blue uniform, with a sword in his hand, ran upon him, shouting something. Pierre, instinctively defending himself from the shock, as they, having not seen, fled against each other, put out his hands and grabbed this man (it was a French officer) with one hand on his shoulder, the other on proudly. The officer, firing his sword, grabbed Pierre by the scruff of the neck.

For a few seconds they both looked with frightened eyes at faces alien to each other, and both were at a loss about what they had done and what they should do. “Am I captured or is he captured by me?” - each of them thought. But, obviously, the French officer was more inclined to think that he was taken prisoner, because Pierre's strong hand, driven by involuntary fear, gripped his throat more and more tightly. The Frenchman wanted to say something, when suddenly over their heads the core whistled low and terribly, and Pierre thought that the head of the French officer was torn off: so quickly he bent it.

Pierre also bent his head and let go of his hands. Without thinking anymore about who captured whom, the Frenchman ran back to the battery, and Pierre down the hill, stumbling over the dead and wounded, who seemed to him to catch him by the legs. But before he had time to go downstairs, dense crowds of running Russian soldiers appeared towards him, who, falling, stumbling and screaming, cheerfully and violently ran to the battery. (This was the attack that Yermolov attributed to himself, saying that only his courage and happiness could make this feat possible, and the attack in which he allegedly threw the George Crosses in his pocket on the barrow.)

The French, occupying the battery, ran. Our troops, shouting "Hurray," drove the French so far behind the battery that it was hard to stop them.

The prisoners, including the wounded French general, who was surrounded by officers, were brought from the battery. Crowds of wounded, acquaintances and strangers to Pierre, Russians and French, with faces disfigured by suffering, walked, crawled and rushed from a battery on a stretcher. Pierre entered the mound, where he spent more than an hour, and from the family circle that took him to him, he did not find anyone. There were many dead, unfamiliar to him. But he recognized some. The young officer sat curled up at the edge of the shaft in a pool of blood. The red-haired soldier was still twitching, but he was not removed.

Pierre ran down.

“No, now they will leave it, now they will be horrified at what they have done!” Thought Pierre, aimlessly following the crowds of stretchers moving from the battlefield.

But the sun, covered with smoke, stood still high, and in front, and especially to the left of Semenovsky, something was boiling in the smoke, and the rumble of shots, shooting and cannonade not only did not subside, but intensified to desperation, like a man who, tearing himself, screaming with all his might.

The main action of the battle of Borodino took place in the space of a thousand fathoms between Borodin and the flashes of Bagration. (Outside this space, on the one hand, the Russians made a demonstration by the cavalry of Uvarov on the one hand in the afternoon, and on the other hand, behind Utitsa, there was a clash between Poniatowski and Tuchkov; but these were two separate and weak actions in comparison with what happened in the middle of the battlefield. ) On the field between Borodin and the flushes, near the forest, on an open and visible from both sides, the main action of the battle took place, in the simplest, most ingenious way.

The battle began with a cannonade on both sides of several hundred guns.

Then, when the smoke covered the whole field, two divisions, Desse and Kompana, flushed to the right and two regiments of the vice king to Borodino moved to this smoke (from the French side) on the right.

From the Shevardinsky redoubt, on which Napoleon stood, the flushes were at a distance of a mile and Borodino more than two miles in a straight line, and therefore Napoleon could not see what was happening there, especially since the smoke, merging with the fog, hid all the terrain. The soldiers of the Desse division, aimed at flushes, were visible only until they went down to the ravine that separated them from the flush. As soon as they descended into the ravine, the smoke of gun and gun shots on the flushes became so dense that it blocked the entire rise of that side of the ravine. Something black flashed through the smoke - probably people, and sometimes the gleam of bayonets. But whether they were moving or standing, whether it was the French or the Russians, it was impossible to see from the Shevardinsky redoubt.

The sun rose light and slanted beams directly into the face of Napoleon, who looked from his hands at the flushes. Smoke fell before the flushes, and it seemed that the smoke was moving, it seemed that the troops were moving. Sometimes people heard cries from the shots, but it was impossible to know what they were doing there.

Napoleon, standing on the mound, looked into the chimney, and in the small circle of the chimney he saw smoke and people, sometimes his own, sometimes Russian; but where was what he saw, he did not know when he looked again with a simple eye.

He came down from the mound and began to walk back and forth in front of him.

Occasionally he stopped, listened to the shots and peered into the battlefield.

Not only from the place below, where he stood, not only from the mound, on which some of his generals were now standing, but also from the very flushes on which were now together and alternately Russian, French, dead, wounded and alive, scared or maddened soldiers, it was impossible to understand what was being done at this place. For several hours at this place, among the incessant firing, gun and cannon, some Russians, then French, then infantry, or cavalry soldiers appeared; appeared, fell, shot, collided, not knowing what to do with each other, shouted and ran back.

From the battlefield, his adjutants and ordinaries of his marshals constantly reported to Napoleon with reports on the progress of the case; but all these reports were false: both because in the heat of battle it is impossible to say what is happening at this moment, and because many adjuttants did not reach the real place of the battle, but transmitted what they heard from others; and also because while the adjutant was passing by the two three versts that separated him from Napoleon, the circumstances changed and the news that he was carrying was already becoming incorrect. So the adjutant jumped from the vice king with the news that Borodino was busy and the bridge on Koloch was in the hands of the French. The adjutant asked Napoleon if he would command the troops? Napoleon ordered to line up on that side and wait; but not only while Napoleon was giving this order, but even when the adjutant had just left Borodin, the bridge had already been repelled and burned by the Russians, in the very battle that Pierre had participated in at the very beginning of the battle.

The adjutant, jumping up from a flash with a pale, frightened face, informed Napoleon that the attack was repelled and that Kompan was wounded and Davout was killed, while the flashes were occupied by another part of the troops, while the adjutant was told that the French were repulsed, and Davout was alive and only slightly shell-shocked. Conscious of such necessary false reports, Napoleon made his orders, which were either already executed before he made them, or could not be and were not executed.

Marshals and generals, who were closer to the battlefield, but like Napoleon, who did not participate in the battle and only occasionally drove into the fire of bullets without asking Napoleon, made their orders and gave their orders about where and where to shoot, and where to ride horseback, and where to run on foot soldiers. But even their orders, just like the orders of Napoleon, in the same way, to the smallest degree, were rarely enforced. For the most part, it turned out to be contrary to what they ordered. The soldiers, who were ordered to go forward, having fallen under a shot by a shot, fled back; the soldiers, who were ordered to stand still, suddenly, seeing the Russians suddenly appearing against themselves, sometimes fled back, sometimes rushed forward, and the cavalry galloped without orders to catch up with the fleeing Russians. So, two regiments of cavalry galloped across the Semenovsky ravine and had just entered a mountain, turned around and galloped backwards. Infantry soldiers moved in the same way, sometimes running at a completely different place where they were told. All orders about where and when to move the guns, when to send foot soldiers — to shoot, when horseback — to stomp Russian pedestrians — all these orders were made by the closest unit chiefs who were in the ranks, not even asking Ney, Davout and Murat, not only Napoleon. They were not afraid of punishment for non-execution of orders or for unauthorized orders, because in a battle the matter concerns the person most dear to them - their own life, and sometimes it seems that salvation consists in running backwards, sometimes in running forward, and these people acted in accordance with the mood of the minute who were in the heat of battle. In fact, all these movements back and forth did not facilitate or change the position of the troops. All their attacks and bumping into each other almost did no harm to them, and the kernels and bullets that flew everywhere through the space through which these people darted caused harm, death and mutilation. As soon as these people left the space through which the cores and bullets flew, the chiefs immediately standing behind them formed, subordinated to discipline and, under the influence of this discipline, entered again into the area of \u200b\u200bfire, in which they again (under the influence of the fear of death) lost discipline and rushed about the random mood of the crowd.