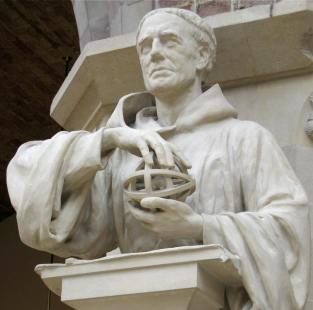

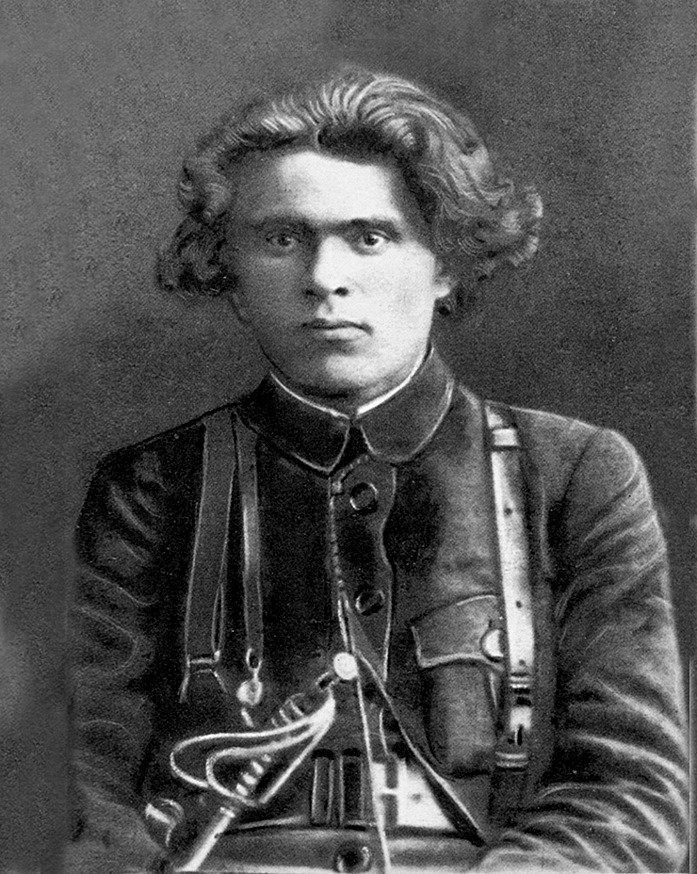

Roger Bacon Biography: “An amazing doctor.” Middle Ages

Roger Bacon (circa 1214, Ilchester County Somerset, England - 1292, Oxford, England), also known as the Amazing Doctor (Latin Doctor Mirabilis) - English philosopher and naturalist, Franciscan monk (since 1257); professor of theology at Oxford. He was engaged in mathematics, chemistry and physics; in optics, he developed new theories about magnifying glasses, refraction of rays, perspective, the magnitude of visible objects, and others.

In philosophy, Bacon did not create a new doctrine, but criticized the methods and theories of his time, which claimed that philosophy had already reached perfection; the first to speak out against scholasticism and spoke sharply about the great authorities of that time (Alberta the Great, Thomas Aquinas, and others); this circumstance, in connection with his attacks on the licentiousness of the clergy, brought on him the persecution of spiritual authority and a 12-year prison sentence. His work “Opus majus” (1268) holds the idea of \u200b\u200bthe futility of abstract dialectics, the need to study nature through observation and subject it to the laws of mathematical calculation.

He believed in astrology, in omens, in a philosopher's stone and in the quadrature of the circle; author of small works on alchemy. The mention of the “Secret” in the composition of “Opus Tertium” proves its belonging to a limited circle of esotericists (who possessed a philosopher's stone and knew a hidden secret).

Books (1)

Favorite

This publication presents for the first time to the Russian reader the works of the famous English theologian, philosopher and natural scientist, Franciscan monk Roger Bacon (c. 1214 - after 1292).

R. Bacon is known as one of the forerunners of the methodology of modern science. Criticizing the scholastic methods of cognition characteristic of the 13th century, R. Bacon emphasizes the importance of mathematics, astronomy, geography, and philology to achieve true knowledge. He devotes much attention to experience as a criterion of truth. This publication includes fragments of the most famous work of R. Bacon - "Opus maius" ("The Great Composition"), as well as his work "On the secret deeds of art and nature and the insignificance of magic."

Roger Bacon

(Latin Rogerius Baco, English Roger Bacon, French Roger Bacon)

(circa 1214, Ilchester, Somerset, England - after 1292, Oxford, England)

Bacon or Bacon Roger. XIII table. - a century, especially rich in great people, and Roger B., as the son of this century, occupies a prominent place between such thinkers as Albert the Great, Bonaventure, Thomas Aquinas. The merits of the latter were appreciated during their lifetime, while R. B. was for a long time neglected, and contemporaries did not at all manage to evaluate him as a thinker. Only recently, criticism restored the value of B., but at the same time carried away in the opposite extreme, exaggerating its value. If R. B. was not appreciated by contemporaries, it was only because he excelled in their development. He can be called a philosopher of the XVI and XVII centuries, abandoned by fate in the XIII century. As a thinker, R. B. stands incomparably higher than some of his famous namesakes. Dühring gives us such an opinion about B. in his Critical History of Philosophy (Dühring, Critische Gesch. D. Phil., 192, 249). In this assessment of B. there is some truth, but a lot is exaggerated. The works of R. B. were not distinguished by originality; in it we do not meet clear creative thoughts or a research method such that science could take a different direction. He was rather a shrewd and systematic thinker and worked on a well-beaten track, on a track with which his contemporaries were knocked down by the seductive arguments of theologians and metaphysicians.

Roger B. was born in 1214 near Ilchester in Sommersetshire, in a wealthy family. R. B. himself spent a lot of money on books and tools. During the turbulent reign of Henry III, B.'s family was badly damaged, property was ravaged, and some members of the family were exiled. Roger B. graduated from his education in Oxford, and not in Merton and Brazenos, as some say, since the last colleges did not exist at that time. Very little information has reached us about B.'s life in Oxford. It is said that in 1233 he accepted monasticism, and this news is not without likelihood; the next year, or maybe later, he goes to France and has been studying for a rather long time at the University of Paris - the then center of thinking Europe. The years B. spent in France were unusually lively. Two large monastic orders - Franciscans and Dominicans - were at that time in full force and gave direction to theological disputes. Alexander of Hales, author of the great Summa, was a representative of the Franciscans, while the other order had a representative of Albert the Great and an ascendant genius, Dr. Thomas Aquinas. A systematic study of Arab writers opened B.'s eyes to the error of these scholars. He clearly recognized the fallacy of his contemporaries when they claimed that philosophy had already reached perfection. The great authority of that time, Aristotle, on which they were mainly based, was poorly understood by them, since his works reached them in distorted translations. Most scholars from B.'s contemporaries knew the Greek language so poorly that it was difficult and impossible for them to understand the thoughts of Greek philosophers in their entire essence. The works of philosophers, if they were read in schools, were read on distorted translations or in incorrect publications; physical knowledge was developed not by experiments, as Aristotle required, but by disputes and arguments based on authority or custom. Everywhere there was an apparent knowledge that covered complete ignorance. Roger B. was so superior to his contemporaries that he could distinguish true knowledge from false knowledge and, having a vague idea of \u200b\u200bthe scientific method, bravely departed from the scholastic routine and devoted himself to the study of languages \u200b\u200band experimental research. Among all the professors with whom he had to deal in Paris, only one deserved his sympathy and respect, namely Peter from the Maharikuria Picardus (Petrus de Maharusuria Picardus), i.e. the Picardian. The identity of this Picardus is little known, but in all likelihood it was none other than the mathematician Peter Peregrinus of Picardy, the author of a treatise on a magnet, the manuscript of which is stored in the National Library in Paris. The unknownness of this scientist and the undeserved fame used by school professors aroused indignation of Bacon. In his Opus Minus and Opus Tertium, he fiercely attacks Alexandre Hales, and in particular another professor who is not named. This anonymous writer, according to Bacon, who did not receive a special and systematic education, joined the order in his young years and began to teach philosophy here. The strictly dogmatic and confident nature of his lectures raised his significance in Paris to the point that he was compared with Aristotle, Avicena and Averroes. In fact, without sufficient scientific background, he harmed the true understanding of philosophy more than anyone else. His confidence and aplomb reached the point that, having no clear and definite idea of \u200b\u200beither the property of light or perspective, he wrote a treatise: “De naturalilbus”. True, he read a lot, observed and was familiar with applied knowledge, but the whole reserve of his information could not bring significant benefits to science, since he had no idea about the true method of research. It is difficult to determine who this unknown scientist was. Brever believes that this is Richard of Cornwallius; but the little that is known about Richard does not agree with Brever’s opinion, as well as with what is said about him elsewhere in B. Erdman sees Thomas Aquinas here, which is also incredible, since Thomas was not among the first, studied and taught philosophy in the order. Cousin and Charles think that this is Albert the Great, and indeed much said by Bacon is applicable to him, but very much does not apply to him at all. Anonymous is said to have received no philosophical education, while Albert, as established, received one; finally, the unknown, according to B., entered the order in his young years, while Albert, if his birth date is shown correctly, entered the order 29 years of age. Similarly, one cannot say about Albert that he was not knowledgeable in alchemy, since his inventions in this field are well known. In general, this question remains unresolved. There is evidence to suggest that B. during his stay in Paris gained fame. He received a Ph.D. and earned the honorary title of “doctor mirabilis”. In 1250, B. returned to Oxford again and, probably, at the same time entered the Franciscan order. B.'s fame quickly spread to Oxford, although it was somewhat overshadowed by suspicions of a penchant for black magic and an apostasy from the dogmas of the true church. Around 1257, the general of the Order of Bonaventure stopped his lectures at Oxford and ordered him to leave the city and placed it under the supervision of the order in Paris. Here he remained under supervision for 10 years, suffered hardships and was unable to publish anything written by him. But during his stay in Oxford, his fame reached the papal legate in England, Guy de Foulques, a man educated and inclined to science, who in 1265 reached the papal throne under the name of Clement IV. The following year, he wrote to B., with whom he was always in relations, so that, despite the prohibitions of his superiors, he would send him scientific notes, which he had already demanded of him once, as a papal legate. B., having lost hope of publishing anything from his works, perked up, having received a similar request from the pope. Despite the mass of obstacles that were made to him by envious leaders and a monastic brotherhood, despite the lack of funds and the inability to find skilful scribes, B., encouraged by a powerful patron, composed three large treatises over the course of 18 months: “Opus Majus”, “Opus Minus” and the Opus Tertium, which, together with other tracts, was delivered to the pope through a young man, Johannes, brought up and trained with great care by Bacon himself. To write an essay of such a volume and in such a short time was, of course, a great feat. It is not known what opinion of him was made by Pope Clement IV, but until his death he was interested in the fate of B. and patronized him. It must be assumed that thanks to this patronage B. in 1268 received permission to return to Oxford. Here he continued his studies in experimental sciences, and also worked on the compilation of complete and completed treatises. B. looked at his work sent to him by Clement IV as the basic principles that subsequently should be applied to the development of all sciences. The first part of Bacon’s work came to us under the name: “Compendium Studii philosophiae” and dates back to 1271. In this essay, Bacon makes sharp attacks on the ignorance and depravity of the clergy and monks, and generally on the insufficiency of existing knowledge. In 1278, B. was temporarily persecuted for the courage of his convictions, which at that time was still practiced for the first time. His books were confiscated by Jerome of Ascoli, general of the Order of the Franciscans, a severe hypocrite, who subsequently ascends to the papal throne. The unfortunate philosopher was imprisoned, where he spent 14 years. During these years he wrote, as they say, a small treatise "De Retardandis Senectutis Accideutibus", but, in all likelihood, this news is hardly true. In 1262, when, as they think, B's last work: Compendium Studii Theologiae appeared, he was already free again. The exact time of his death cannot be determined; 1294 is the most suitable time to which it can be attributed.

Works of R. Bacon extremely numerous. They can be divided into two categories: those remaining so far in manuscripts and printed. A huge number of manuscripts are in British and French libraries, between which there are many valuable works in the sense that they explain the essence of Bacon's philosophy. Excerpts from these works were made by Charles, but it is clear that a complete picture of his philosophy is unthinkable until all his works have been published. More important manuscripts: Communia Naturalium (located at the Mazarini Library in Paris, at the British Museum, at the Bodleian Library and at the University College Oxford Library); "De Communibus Mathematicae", part of it is in the collections of Sloane (Sloane), that is, in the British Museum, part in the Bodleian library; Baconis Physica is located between supplementary manuscripts in the British Museum; excerpts “Quinta Pars Compendii Theolögiae” - in the British Museum; "Metaphysics" in the National. library in Paris; Compendium Studii Theolögiae, at the British Museum; excerpts from the logic of Summa Dialectices, in the Bodleian Bible. and interpretations on the physics and metaphysics of Aristotle in the library in Amiens.

Compositions printed: “Speculum Alchimiae” (1541, translated into English in 1597); “De mirabili potestate artis et naturae” (1542, English translation 1659); “Libellus de retardandis senectutis accidentibus et sensibus confirmandis” (1590, translated into English, like “Cure of Old Age”, 1683); "Medicinae magistri D. Rog. Baconis anglici de arte chymiae scripta ”(1603, collection of small tracts containing“ Excerpta de libro Avicennae de Anima, Brève Breviarium, Verbum Abbreviatum ”, at the end of which there is a strange note ending with the words:“ Ipse Rogerus fuit discipulus Alberti! ” ); “Secretum Secretorum, Tractatus trium verborum et Speculum Secretorum”); Perspectiva (1614, makes up the fifth of the Opus Majus); “Specula Mathematica” (constitutes the fourth part of the same work); "Opus Majus ad Clementem IV" (published by Jebb, 1733); "Opera hactenus inedita" (J. S. Brever, 1859, containing "Opus Tertium", "Opus Minus", "Compendium studii philosophiae" and "De secretis operibus naturae").

Bacon's small works on alchemy are not so important, and the time when they were written cannot be determined with accuracy. In any case, B.'s outstanding literary activity begins with the publication of his work: "Opus Majus." This work is called the Wevel (Whewell) together with the Encyclopedia and Organon of the thirteenth century. As published by Jebb, it consists of six parts, although you can find the seventh - “On moral philosophy” (De morali philosophia), which is often referred to as “Opus Tertinm”.

Part I (p. 1-22) is often called the “De Utilitate Scientiarum”, which refers to the four offendicula, or causes of error. They are the essence: authority, habit, opinions of the uneducated majority and a mixture of complete ignorance with apparent knowledge or a claim to knowledge. The latter error is the most dangerous and, in some respects, the cause of other errors. Offendicula R. B. were the forerunners of the more famous theory of idols (Idola) by Francis B. In the general conclusion of this part, which was made by B. in "Opus Tertium", Bacon's view on the need for a unity of sciences clearly stands out.

Part II (pp. 23-43) deals with the relationship between philosophy and theology. True wisdom is in st. The scriptures. The task of this philosophy should be that humanity has reached a perfect understanding of the creator. Ancient philosophers who did not have Scripture received revelation directly from God and only those achieved brilliant results who were chosen by Him.

Part III (pp. 44-57) contains a discussion about the benefits of grammar and the need for true philology for a true understanding of St. Scripture and Philosophy. Here B. points out the necessity and benefit of studying foreign languages.

Part IV (pp. 57-255) contains the processed treatise "On Mathematics" - this "ABC of Philosophy" and its importance in science and theology. According to B., all sciences are based on mathematics and only then progress when facts can be summed up as mathematics. principles. B. confirms these original thoughts with examples, showing, for example, the application of geometry to the action of natural bodies, and demonstrates some cases of the application of the law of physical forces by geometric figures. Further, he explains how his method can be applied to certain issues, such as, for example, the light of stars, the ebb and flow of the ebb, and the movement of the scales. Then B. tries to prove, although he does not always succeed, that knowledge of mathematics is the basis of theology. This section of B.'s work ends with two beautifully presented essays on geography and astronomy. The geographical sketch is especially good and interesting in that Columbus read it and this work made a strong impression on him.

Part V (pp. 256-357) is devoted to a treatise on perspective. Bacon was especially proud of this part of his work, but it should be noted that the writings of the Arabic writers Alkind and Algazen helped him a lot. The treatise begins with a skilful psychological essay, partly based on the Aristotelian De Anima. Then the anatomy of the eyes is described; this part is obviously processed independently; then Bacon dwells in great detail on the question of reflection in a straight line, on the law of image and reflection, and on the construction of simple and spherical mirrors. In this part, as in the previous one, his reasoning is based mainly on his personal views on the forces of nature and their actions. His main physical positions are matter and forces, the latter he calls: virtus, species, imago agentis, and many others. Changes or some natural process occurs through the action of virtus or species on matter. The physical action from here is the impression or transition of force into a line and therefore must be explained by geometry. Such a view of Bacon on nature passes through his whole philosophy. To the small notes on this subject set forth in the 4th and 5th hours of the Opus Majus, he adds two or three independent sketches. One of them is set forth in the treatise “De multiplicatione specierum”, published by Jebb, as part of “Opus Majus” (pp. 358-444). To get acquainted with the question of how the theory of nature is consistent with the metaphysical problems of force and matter, with the logical doctrines of the universe and, in general, with Bacon’s theory, it is necessary to turn to the publication of Charles.

Part VI (pp. 445-477) talks about the experimental sciences of Domina omnium Sclentiarum. Two research methods are proposed here: one by reason, the other by experiment. Pure arguments are never sufficient, they can solve the issue, but they do not give confidence to the mind, which is convinced and satisfied only by immediate verification and investigation of the fact, and this is achieved only by experience. But the experience can be twofold: external and internal; the first is the so-called. ordinary experience, which cannot give a complete picture of visible objects, and even more so about mental objects. In inner experience, the mind is usually enlightened by divine truth, and in this supernatural enlightenment there are seven degrees. The views on the experimental sciences, which in Opus Tertium (p. 46) sharply separate B. from speculative sciences and craft art (applied, professional), strongly resemble the opinions of Francis Bacon on the same issue. Experienced sciences, says Roger B., have three advantages over other sciences: 1) they test their conclusions by direct experience; 2) they reveal truths to which they could never have reached; 3) they seek out the secrets of nature and introduce us to the past and future. The basis of his method B. puts a study of the nature and causes of the origin of rainbow colors, which really is an excellent example of inductive research.

Seventh was not included in the Jebb edition, but is mentioned at the end of the Opus Tertium (chapter XIV). Excerpts from it can be found in Charles (pp. 339-348). B. had not yet finished his enormous work, when he had already begun to prepare a conclusion to him, which was to be sent to Clement IV along with his main work. From this conclusion, or “Opus Minus,” a part has come down to us and entered into “Op. Inedita »Brever (313-389). The composition of this work was to include an extract from the Opus Majus, a collection of the main errors of theology, a discussion of speculative and practical alchemy. At the same time, B. begins the third essay, as it were, a preface to the first two, explaining their common goal and task and supplementing them in many ways. Part of this work is usually called. "Opus Tertium" and was printed by Brever (pp. 1-310), who believes that it is a separate and completely independent treatise. Charles, on the other hand, considers him only as a preface and gives quite good reasons. In this composition, according to Charles, we are talking about grammar, logic (which B. considers unimportant, since reasoning is a natural thing), about mathematics, general physics, metaphysics and moral philosophy. Charles finds confirmation of his conjectures in certain parts of Communia Naturalium, which clearly prove that this essay was sent to Clement, and therefore could not be part of Compendium, "but, as Brever thinks. It should be noted that there is nothing more confusing as a question about the relation of B.'s works to each other, and this will continue until all the texts of his works are collected and printed.

Roger B.'s fame is based mainly on his mechanical inventions, although the latest research on B.'s life and inventions diminishes his importance in this area. Bacon gives the theory and method of telescope construction, but the description is so unsatisfactory that one cannot be sure that he possesses such a tool. Gunpowder, the invention of which was also attributed to him, was already known to him by the Arabs. That place in B.'s work, which speaks of gunpowder and on the basis of which he was credited with the honor of this invention, can hardly lead to such a conclusion. Incendiary glasses were common; and glasses, presumably, he did not invent, although he should not be denied acquaintance with the law of their device. Paying tribute to the century, B. believed in astrology, in omens, in a philosopher's stone and in the quadrature of the circle. Wed Siebert, Roger W., sein Leben u. seine Philosophie "(Marb., 1661); Charles (Charles), "Roger B., sa vie, ses ouvrages, ses doctrines" (Bruce., 1861); Schneider, “Boger Bacon” (Augsb., 1873); Werner, "D. Kosmologie und allgemeine Naturlehre des Roger B. "(Vienna, 1879). See also Encyclopaedia Britannica (vol. III, 1888).

(Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron. T. IIa, p. 744-748)

Bacon, Bacon Roger (c. 1214, Ilchester, Somerset – 1294 County, Oxford) is an English natural philosopher and theologian, Franciscan, “an amazing doctor” (doctor mirabilis). Studied at Oxford with Robert Grossetest

and Adam from Marsh until 1234, then in Paris, where he listened Alexander Gelsky

, Albert the great

, Guillaume

from Auvergne. He taught in Paris, from 1252–57 at Oxford; about the subject of teaching can be judged by his comments on the book. I – IV of Aristotle's “Physics”, Prince XI "Metaphysics". Then, possibly due to political changes, he left England. Franciscan "spiritualist" party, worried about apocalyptic moods in the spirit Joachim of Flore

,

Bacon was subjected to disciplinary measures (“prelates and brothers, languishing in my fasting, kept me under surveillance”) by the party that took over Bonaventure

.

Between 1265 and 1268, at the request of Pope Clement IV, he hastily expounds his doctrine in the so-called "Great Labor" with the introductory "Third Labor" and the fragmentary "Small Labor" adjacent to it. In 1272 he wrote the philosophical compendium (Compendium studii philosophiae), in 1292 "The Compendium of Theology." It is known that from 1277 or 1278 to 1279 he was imprisoned by the authorities of his order for “some suspicious innovations”, possibly in connection with his defense of astrology, condemned in 1277 by the Paris bishop Etienne Tampier, or in connection with the uprising in Ancona in 1278 after which the Franciscan Order was purged.

Bacon, Bacon Roger (c. 1214, Ilchester, Somerset – 1294 County, Oxford) is an English natural philosopher and theologian, Franciscan, “an amazing doctor” (doctor mirabilis). Studied at Oxford with Robert Grossetest

and Adam from Marsh until 1234, then in Paris, where he listened Alexander Gelsky

, Albert the great

, Guillaume

from Auvergne. He taught in Paris, from 1252–57 at Oxford; about the subject of teaching can be judged by his comments on the book. I – IV of Aristotle's “Physics”, Prince XI "Metaphysics". Then, possibly due to political changes, he left England. Franciscan "spiritualist" party, worried about apocalyptic moods in the spirit Joachim of Flore

,

Bacon was subjected to disciplinary measures (“prelates and brothers, languishing in my fasting, kept me under surveillance”) by the party that took over Bonaventure

.

Between 1265 and 1268, at the request of Pope Clement IV, he hastily expounds his doctrine in the so-called "Great Labor" with the introductory "Third Labor" and the fragmentary "Small Labor" adjacent to it. In 1272 he wrote the philosophical compendium (Compendium studii philosophiae), in 1292 "The Compendium of Theology." It is known that from 1277 or 1278 to 1279 he was imprisoned by the authorities of his order for “some suspicious innovations”, possibly in connection with his defense of astrology, condemned in 1277 by the Paris bishop Etienne Tampier, or in connection with the uprising in Ancona in 1278 after which the Franciscan Order was purged.

All the works of Bacon - outline-prospectuses of the unwritten "main work", the sum of all knowledge; in the ideal of “aggregate wisdom”, Bacon sees the influence of the mystical pseudo-Aristotelian medieval treatise Secret Secretorum. Conscious of the insufficiency of solitary effort in such a large undertaking, even in concrete scientific analyzes, Bacon gravitates toward the persuasio genre in the hope of persuading his father or others to finance his project. Not a single private science has an independent value for it, it is like a “torn eye” if it is not directed in alliance with others to “benefit” - the highest goal that organizes all sciences from the outside into a single body of knowledge in the same way that an architect gives meaning to private "Operations" of builders. If the ultimate task does not lead the seeker at every step, the students' interest will soon run out “on the fifth Euclidean theorem”, the mind will become bogged down in the wilds and “will disgust with disgust” even what it perceived.

Bacon expands the “grammar” in its traditional role as the beginning of all teachings, requiring the compulsory development of not only Latin, but also Greek, Arabic, Jewish languages. Aristotle and the “commentator” (Avicenna) should be read in the original, all Latin translations are teeming with errors and misinterpret the essence, it would be more useful to burn them. Acquaintance with other worlds helps Bacon to conduct an unprecedentedly sharp criticism of Latin Europe as just one of the cultures, which is far inferior to pagan antiquity in the beauty of moral virtues, lagged behind the Arab world in the study of nature, especially in the manufacture of mathematical and astronomical instruments, mired in destructive for the philosophy of idle talk of Parisian professors, in the useless verbosity of preachers, is physically degenerating due to the decline of practical medicine.

The base of knowledge is mathematics. Its axioms are innate to man, she disposes us, providing transparency of what is comprehended, to other sciences up to philosophy: “Without mathematics, it is impossible to know the heavenly, and the heavenly is the cause of what is happening in the lower world, but the cause cannot be known without passing through its causes.” Most of Bacon’s research is devoted to optics (“perspective”; by 1267, he said, he had been doing it for 10 years). His works on the ray and the spectrum of the decomposition of light occupy a prominent place in the history of medieval optics, while in other sciences he uses mainly the achievements of his era. True, in the field of optics, Bacon owes a lot to Al Haysam. Following Robert Grossetest, he develops the neo-Platonic-Augustinian metaphysics of light as the primary substance of the universe. Everything in it is known through perspective, for "all influences are accomplished through the reproduction (radiation) of species and energies by the active forces of our world in perceiving matter." The “crowd of philosophers” “wanders meaninglessly in the fog” due to ignorance of perspective. The latter in Bacon is not inferior in importance alchemy - both theoretical, interpreting the principles of substances, and practical, manufacturing precious metals, paints, etc. better than nature.

All human knowledge is guided and applied by experimental science (scientia experimentalis), which in Bacon has a broad sense of mastering the forces of nature. She opposes his magic and is designed to surpass the latter in miracles, relying not on magic, but on art and research "of countless things with exceptional energies, the properties of which are unknown to us solely because of our laziness and negligence in our searches." Although experimental science requires thousands of workers and colossal means, “treasures of the whole kingdom,” it will not only pay for all expenses for itself, but for the first time it will justify the very existence of philosophy, which still lives on credit and attracts fair reproaches for its futility. Among the expected achievements of a true experimenter, Bacon names an incendiary mirror that burns without fire at any distance military camps of the Mongols and Saracens; flying, underwater swimming devices; light storage substances; drugs to extend human life to hundreds of years; detailed maps of celestial movements, allowing you to calculate all past and future events; artificial precious metals in any quantities; finally, man-made miracles capable of convincing non-believers of the superiority of Christians over missionaries of other religions.

Regal experimental science, however, remains speculative in comparison with a genuinely higher and only practical moral philosophy. In the first place among the good deeds of this “mistress of all parts of philosophy” is the streamlining of the state as a huge machine so that “no one is idle”, and most importantly, the selection of gifted youth and intensive teaching of its sciences and arts “for the common good” ". The revival of morality is all the more necessary because knowledge penetrates only into a pure soul. Only she is able to accept the illumination from above and formalize her potencies with the energies of the active intellect (intellectus agens), by which Bacon means divine wisdom. The depths of knowledge will be revealed only to Christians, and Bacon is confident in the worldwide spread of Catholicism through the subjugation, destruction, or conversion of Gentiles. Judging by the "corruption that has gone to extremes" of a human being and believing Merlin's prophecies, Bacon expected from year to year the coming of the Antichrist, the battle of Christians with him and the subsequent renewal of the world. Hence the project of the scientific and moral arming of the Christian people for the sake of the universal "state of the faithful" under the leadership of the pope.

The successor of Bacon’s science can be considered Leonardo da Vinci with his distrust of abstract science, focus on practical invention. Close to R. Bacon's Positions F.Bacon with his empirical science, Descarteswith his mathematization of knowledge. 16th-century naturalists turned to the "magic" subjects of Bacon, looking for natural paths to the wonders of alchemy. Today, Bacon is the subject of lively philosophical discussion in connection with the problems of modern Jewish science.

Works:1. The opus maius, transl. by R.В .Burke, vol. 1-2. Phil., 1928; 2. Opus maius, vol. I – III, ed. J.H. Bridges. Oxf., 1897–1900, repr. Fr./M., 1964; 3. Opus maius, pars VI: Scientia experimentalis. Columbia, 1988; 4. Operis maioris pars VII: Moralis philosophia, ed. E. Massa. Ζ., 1953; 5. Opera hactenus inedita, ed. R. S.teele, F. M. Delorme, fasc. 1-16. Oxf., 1905–40; 6. Compendium studii theologiae, ed. H. Rashdall. Aberdeen, 1911, repr. Farnborough, 1966; 7. An inedited part of Roger Bacon’s Opus maius: De signis, ed. Nielsen L. Fredborg and J. Pinborg. - "Traditio", 1978, vol. 34, p. 75-136; 8. in Russian trans.: Anthology of world philosophy, vol. 1, part 2. M., 1969.

Literature:1. Akhutin A.V.History of the principles of a physical experiment. M., 1976, p. 145-164; 2. Gaidenko P. nbsp; P.The evolution of the concept of science. M., 1987; 3. Keyset S. J. Roger Bacon. Amst., 1938; 4. Crowley t. Roger Bacon. Louvain-Dublin 1950; 5. Easton S. C Roger Bacon and his search for a universal science. Oxf., 1952; 6. Alessio f. Mito e scienca in Ruggero Bacone. Mil., 1957; 7. Heck e. Roger Bacon. Ein mittelalterlicher Versuch einer historischen und systematischen Religionswissenschaft. Bonn, 1957; 8. Bérubé C. De la philosophie à la sagesse chez saint Bonaventure et Roger Bacon. Roma, 1976; 9. Lértora M. La infinitud de la aterial segun Roger Bacon. - "Revista filosofica Mexicana", 1984, vol. 17, n. 49, p. 115–134.

V.V. Bibikhin// New philosophical encyclopedia: In 4 vols. / Institute of Philosophy of the Russian Academy of Sciences,

Nat general scientific fund. T. I. M., 2010.S. 348-350.

TEXTS

“Alchemical miscellany” - a manuscript of the 16th century, which includes an English translation of the work of R. Bacon “Radix mundi” ( Roger Bacon or Johannes Sawtre, Radix mundi, translated into English by Robert Freelove, 1550.)

Opus Majus / Ed. by J. H Bridges. Oxford, 1897.

(1214-1292)

"No knowledge can be sufficient without experience."

Like Albert and his other contemporaries, Roger Bacon, a member of the monastic order of the Franciscans, relied in his scientific research on the philosophy of Aristotle. At the same time, he not only drew wisdom from philosophical observations and reasoning, but, like Albert, attached great importance to experiment. But it should be remembered that today we put in the concept of experience a completely different meaning than it had in the Middle Ages. For example, Bacon states: "We have established from experience that stars cause birth and decay on earth, as is obvious to everyone." For us this is not so obvious at all, and we have the right to ask ourselves how Bacon was able to experimentally discover the mystical influence of stars on the life and death of a person. But Brother Roger, without hesitation, concludes: “Since we have established from experience what philosophers made obvious earlier, it directly follows from this that all knowledge here, in the world, rests on the power of mathematics.”

Another example of Bacon's peculiar approach to a scientific experiment is his experience with hazel. In his book On Experimental Science, he proposes to separate the year-old shoot from the hazel root. This branch should be split lengthwise and given parts of it to two participants in the experiment. Each should hold its part of the branch at two ends; two parts of the branch should be separated by a distance in the palm or four fingers. After some time, the parts themselves will begin to attract each other and, in the end, reunite. The branch will become whole again!

Roger Bacon, English philosopher and naturalist, Franciscan monk.

The “scientific” explanation of this phenomenon, “more surprising than anything I've ever seen or heard,” Bacon borrows from Pliny, completely sharing the views of the latter: some objects, even when separated in space, are mutually attracted.

This explanation is based on the principle of sympathetic magic: like attracts like. But if someone told Bacon that this is magic, he would be very surprised, for he concludes his story about the wonderful properties of the hazel with the following words: “This is an amazing phenomenon. Mages conduct this experiment by repeating all kinds of spells. I cast these spells and found that in front of me was a miraculous action of natural forces, similar to the action of a magnet on iron. " Thus, according to Bacon, magicians are unworthy charlatans: they mutter spells, although they know very well that they demonstrate a natural phenomenon - "as it is obvious to everyone!" This kind of "observation" is often found in the works of Bacon: he condemns magic, while being himself a magician.

History of magic and occultism

Roger Bacon

Biographical information. Roger Bacon (1214-1292) - English Franciscan philosopher. He was educated in Oxford, after that he taught in Paris for about six years, and in about 1252 he returned to England. In 1278, having fallen out of favor with the general of the Franciscan order, he ended up in prison, from where he was released shortly before his death. His nickname was Amazing Doctor.

The main works. The Great Composition (Opus maius), The Small Composition (Opus minus), The Third Composition (Opus tertium). All of them were written in Latin, the last two are preserved only in fragments.

Philosophical views. The problem of knowledge and faith. Science and religion do not contradict each other, the main goal of philosophy is the possible justification of faith. Since miracles do not exist at present, only the path of rational (philosophical) proof and substantiation of truth remains for the conversion of infidels and heretics.

Epistemology. According to R. Bacon, truth is a child of time, and science is the daughter of not one or two scientists, but of all mankind. Therefore, each new generation of people must correct the mistakes made by previous generations. R. Bacon reveals the main causes of human ignorance, which are an obstacle to the truth (tab. 11).

Table 11

Reasons for Human Ignorance

Bacon wrote: “From this deadly plague comes all the misfortunes of the human race, because because of this the most useful, greatest and most beautiful testimonies of the wisdom and mystery of all spiders and arts remain unknown. But even worse, people who are blind from the darkness of these four obstacles do not feel their own ignorance, but with all care they defend and protect it, because they do not find a cure for it. And the worst is that, plunged into the deepest darkness of error, they believe that they are in the full light of the truth. "

Bowing to Aristotle and considering it the most perfect among people, R. Bacon nevertheless maintains that even after the Philosopher (Aristotle) \u200b\u200bthe development of science continues.

According to R. Bacon, there are three sources of knowledge: authority, argumentation (logical conclusion) and experimentbased on experience (Scheme 32). Authority without proof is insufficient. As for the logical conclusion, in itself it is also insufficient if it is not based on experience, since it is impossible to distinguish sophism from proof. “Above all speculative knowledge and art is the ability to make experiments, and this science is the queen of all sciences,” wrote R. Bacon.

He distinguishes two types of experience: interior and external. A person receives inner experience through Divine Revelation, through it we come to comprehension beyond the natural, divine. We get external experience through the senses, through it we come to the knowledge of natural truths. It is on this experience that all sciences must be based.

A special place among all sciences Bacon gives mathematics. He notes that theologians sometimes even consider this science suspicious, because "it had the misfortune to be unknown to the fathers of the church," however, it is very important and useful. The practical benefit that science can bring is what R. Bacon values \u200b\u200babove all (Table 12).

Interestingly, R. Bacon tried to give an astrological (natural science but at that time) explanation of the origin of religions. He identifies several religions known to him: Christianity, Judaism, Islam, the Chaldean religion (apparently, Zoroastrianism), and D. And explains their origin by the specific position of stars and planets. In particular, he associated the emergence of Christianity with a certain conjunction of Jupiter and Mercury.

The fate of the teachings. Bacon did not have much influence on his contemporaries, but he was highly appreciated by the science of the New Age. R. Bacon can be considered the forerunner of the experimental method on which all modern science is built. He considered the goal of all sciences to increase human power over nature. And it is to him that the famous slogan belongs: “Knowledge is power”.

Sciences, their subject and benefits

Table 12

|

The science |

Subject and possible benefits |

|

General theoretical sciencePhilosophy (metaphysics) |

Clarifies the relationship between private sciences and gives them the starting points; itself is based on the results of private sciences |

|

Practical the science Maths |

Learn the nature. He studies numbers and quantities; necessary when building houses and cities, measuring areas and time, creating cars and other |

|

Mechanics (practical geometry) |

With its help, flying vehicles will be created in the future, as well as carriages moving without horses, and ships floating without the help of oars and sails |

|

(perspective) |

He studies the light and its distribution; r. Bacon himself invented glasses, divined the principle telescope and microscope |

|

Astronomy |

Explores the natural powers of stars |

|

Gravity science |

It studies the elements, since in them the main role is played by the difference between the lung and the heavy |

|

He studies inanimate telluric formations and all kinds of elementary combinations of them; you can learn how to turn some elements into others (base metals into gold and silver) |

|

|

Biology (agriculture) |

Studying organic objects, t.s. plants and animals; possibly increased yields, etc. |

|

The medicine |

It studies the human body, its health and disease |

|

Experimental scienceAstrology |

Shows practical consequences from various sciences; allows you to know the past, present and future of earthly events based on astronomical observations |

|

Allows you to create a life elixir, etc. |

Scheme 32. Roger Bacon: Paths of Knowledge

- Anthology of world philosophy: in 4 vols. M., 1979. T. 1. S. 863.

- Cit. by: History of Philosophy. M., 1941.S. 472.

- In the same place. S. 472.

A.S. Gorelov. The philosophy of Roger Bacon and its place in the history of European culture

Introduction

XIII century - The “golden age” of scholasticism was the heyday of a number of philosophical schools and trends, a period when many outstanding thinkers of the Middle Ages lived and worked, including the most famous of the famous - Albert the Great, Bonaventure, Thomas Aquinas, Duns Scott. But even against this bright and varied background, Roger Bacon, nicknamed by his contemporaries Doctor mirabilis - "The Doctor is amazing," continues to amaze current researchers.

His works evoke polar opposite interpretations and evaluations. In the New Age period a widespread image of Roger Bacon appeared as the first modern scientist - a mathematician and a natural scientist-experimenter, who criticized scholastic idle talk and for this suffered from "obscurantists-clergymen." The founder of positivism, Auguste Comte, who proposed a new religion of mankind and, in particular, a calendar project in which months and days would not be called by the names of gods and saints, as before, but by the names of prominent cultural figures, dedicated R. Bacon the first Tuesday of the month “Descartes "(That is, November).

A certain reaction to the positivistic image of R. Bacon was his assessment in the writings of some neo-Thomist historians of philosophy as an unoriginal and ambitious thinker, who became known thanks not to scientific merit, but to a conflicting character and inability to find a common language with contemporaries. Both assessments, of course, are not adequate and in many respects depend on preconceived attitudes: the first on the indiscriminate denial of the Middle Ages as “dark centuries” of culture, the second on the perception of Thomas Aquinas philosophy as the pinnacle of medieval thought, while Roger Bacon has a lot to do with it diverged.

But, even distracting from such extreme judgments, an open-minded researcher is struck by the combination of contradictory features in the work of The Amazing Doctor. Bacon, indeed, was acutely critical of his time: at the same time, he was wholly and completely rooted in him, including in his widespread prejudices. Many of the fruitful ideas expressed by Bacon were often not so original - a careful study shows that some of them go back to his predecessor Robert Grossetest, others to the Arab philosophers, and still others are commonplace in Aristotelianism. Methodological maxims proclaimed by Bacon, such as criticism of false authorities, often do not find application in his own writings, which very often demonstrate, from the current point of view, amazing gullibility in relation to extremely dubious sources.

Bacon proposed large-scale reforms, in the details of which the outlines of the future development of culture are guessed, in particular, the development of natural science and modern technology based on the experience and application of mathematics. But at the same time, his understanding of the words “experience” and “mathematics” is radically different from their modern understanding, and he considered the miraculous inventions predicted by him to be long ago realized, albeit hidden from the ignorant crowd. The idea of \u200b\u200bscientific and technological progress in Bacon, if any, is only in its infancy. In any case, he, like many authors of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, saw the pinnacle of human power not so much in the future as in the past, and sought not to create a new one, but only to restore, at least to some extent, the old power. The main feature of Bacon as a typical thinker of the Middle Ages, and not of the New Age, was that all his philosophical provisions were explicitly inspired by religious considerations.

However, no matter how deeply Bacon is rooted in the worldview of the Middle Ages and no matter how different his activities are from what is commonly called modern science, when reading Bacon you cannot get rid of the sense of originality of the ideas that underlie his grandiose design, and their close connection with the development of those concepts which, developing and changing, eventually became an integral part of the culture of the New Age. Bacon was the first thinker in European history to attempt to create a comprehensive encyclopedia of knowledge, organically combined with theology and focused on achieving practical (religious) goals. This task was not fully implemented by him. Nevertheless, the Bacon project itself, partially embodied in Opus maius, Opus minus, Opus tertium, Compendium studii philosophiae, Compendium studii theologiae, as well as in a number of more specialized works, remained its original contribution to the history of European culture, an important link connecting the Middle Ages and the modern world.

The judgment on the encyclopedic project of Roger Bacon may be hampered by certain features of such compositions as Opus maius, Opus minus and Opus tertium, if you do not take into account the fact that striking heterogeneity of different parts, compositional friability, repetitions, internal contradictions, insufficient study many topics relate to the haste with which Bacon prepared these works for Pope Clement IV, who requested that this be done as soon as possible. In fact, all these works are a compilation of a number of previous works of Bacon, which were in different stages of readiness.

This article does not intend to give a relatively complete picture of the philosophy of Roger Bacon, in particular, due to the large number of diverse topics present in his legacy. Its purpose is to offer an introduction to topics that are one way or another covered in Opus maius and most interesting to a modern non-specialist reader.

The unity of knowledge and the practical goal of philosophy

Bacon did not accept the expressed, in particular, Thomas Aquinas idea of \u200b\u200bthe autonomy of philosophy from theology and in this regard was a typical representative of Augustinism, which dominated among the Franciscan scholars of the XIII century. According to Bacon, “philosophy, consideration” in itself, has no value [...] in philosophy, there can be nothing worthy other than what is required of it for Divine wisdom. And everything else is wrong and empty. ”

Like Aristotle, Bacon distinguished between theoretical and practical (moral) philosophy; for an English philosopher, this distinction looks like this: “theoretical philosophy strives to know the Creator through creation, and moral philosophy establishes purity of morals, fair laws and a divine cult, and also gloriously and usefully exhorts [a person to strive] for the happiness of a future life.” But if Aristotle considered the best way of life contemplative and, accordingly, emphasized the importance of theoretical philosophy, then Bacon preferred moral. All knowledge, in his opinion, has the goal of salvation, achieving eternal life, the means of which are the Church and the Christian state: “the Church of God is built with the light of wisdom, the state of the faithful is built, the faithless are converted, and those who persist in evil can be curbed and squeezed away from the borders of the Church by the power of wisdom, not by the shedding of Christian blood. So, all that requires the guiding force of wisdom comes down to these four things, and with nothing else [t. e. Wisdom] cannot be correlated. ” Moral philosophy, dealing with actions related to good and evil, is primarily called practical, yet other sciences are subordinate to it. However, "practice, understood broadly, is identical to any effective science, and then many other sciences are practical."

According to Bacon, true knowledge is one; this is the knowledge of the one right way of salvation, given to the one world by the one God: "there is one perfect wisdom, which is entirely contained in the Holy Scriptures, and it must be clarified with the help of canon law and philosophy, and thanks to these sciences the interpretation of Divine truth takes place.

Bacon’s conviction that Scripture is the source of all the truth necessary for man, explains the use of the Bible as a source of scientific information, strange enough for the modern era (but not for the Middle Ages), including in physics. For example, Bacon points out that the nature of the rainbow could not be known to either Greek or Arab scholars because it can only be understood on the basis of what was said about the rainbow in the Bible: “I believe My rainbow is in a cloud of heaven ... so that there would be no more flood on The Earth ”(Genesis 9.13), that is, the purpose of the rainbow is the evaporation of water, therefore, when the rainbow appears, there is always scattering of water into countless droplets and their evaporation due to the rays of the Sun, which are concentrated as a result of various reflections and refractions, due to which and a rainbow arises.

Another interesting and historically important example of Bacon’s use of the authority of a biblical book (actually apocryphal) concerns geography: “the tip of India in the East is extremely remote from us and from Spain. But from the tip of Spain on the other side of the Earth [space] for the sea is so small that it cannot cover three quarters of the Earth. [...] So, Ezra says in the fourth book that six parts of the Earth are inhabited, and the seventh is covered with water. ” It is this place, which says that Spain is relatively close to the eastern tip of Asia, determined the interest of Christopher Columbus in opening the western route to India. As you know, instead of Asia, Columbus sailed to an unknown continent at that time - America, although he himself did not know about it until the end of his life.

True philosophy, according to Bacon, is aimed at a Christian, saving goal, even if its positions are found among non-Christian philosophers, to whom Roger Bacon has the deepest respect: first of all, this is Aristotle, but also Seneca, Plato, Socrates, And also Arab commentators and the successors of Aristotle - Avicenna, Averroes, etc.

According to Roger Bacon, Christian thinkers have long rejected non-Christian philosophy for the following reasons: the Fathers of the Church - because it competed with the established Christian faith and was often mixed with false ideas, in particular magical ones; thinkers of the 12th century - based on references to the works of the Church Fathers, not understanding the reasons for their opinions; Bacon's contemporaries - because they "find pleasure in the insignificant and the empty." However, philosophy as such does not at all contradict Christianity. Roger Bacon quotes Augustine: “Christians must take from philosophers - as from illegal owners - the useful things that are contained in their books,” because “the gold and silver of philosophers was not created by themselves, but as if extracted from the universal placers of Divine providence, which spilled everywhere. ”

The presence of elements of divine wisdom among non-Christian philosophers Bacon explains by the fact that all true knowledge is the result of divine enlightenment (illuminatio). This concept is associated with the interpretation of Aristotelian statements about the “acting” and “possible” intelligences in the treatise On the Soul. According to Bacon (as well as many other commentators before him), the “acting” intelligence belongs to God or the angels, and the “possible” to the individual human soul, receiving from God knowledge of certain truths. (There were other interpretations: for example, Thomas Aquinas believed that both intellects belong to the individual human soul, and Averroes - that neither one of them belongs to her, both are common to all mankind).

Unlike Thomas Aquinas, Roger Bacon does not really trust the “natural mind”, does not believe that a person can independently come to deep philosophical truths: as an example of the limitations of human abilities in philosophy, Bacon cites endless debates of scholastics on the famous universal problem. Therefore, Bacon believes that philosophical truths among non-Christians go back to the Old Testament patriarchs and prophets who received Divine Revelation, that is, in a special way enlightened by God (This concept (from the modern point of view, unfounded) has a long history. Ancient Greeks themselves often believed that their philosophers gained their knowledge in the more ancient traditions of the wisdom of the East (see stories about the travels of Thales, Pythagoras, Democritus and others to countries such as Egypt, Palestine, Mesopotamia, India). Subsequently, thinkers of the East, including Judah and (Philo of Alexandria) defended this idea for reasons of national prestige.The Church Fathers (starting with Justin the Philosopher) used the concept of Greek borrowing of philosophy from the Old Testament patriarchs and prophets to legitimize Christianity as “true philosophy” in the eyes of representatives of Hellenistic culture). Thus, the Christian religion represents the completion of a philosophy to which non-Christians are involved. “Unfaithful philosophers even now do not know much of what relates to the Divine; and if such were presented to him as proved by the principles of complete philosophy (that is, by means of viable arguments that originate from the philosophy of the infidels, although they are completed by the faith of Christ) and without contradiction, then they [the unfaithful philosophers] would rejoice the truth he proposed, since they are greedy for wisdom and more educated than Christians. I’m not claiming, however, that they could comprehend something of the spiritual provisions of the Christian faith in the proof, but [I mean] that there are many common rational truths that any sage, without knowing himself, will easily accept from the other. " In modern language, the presence of common philosophical truths among Christians and non-Christians, according to Bacon, forms the basis for inter-religious dialogue, the purpose of which he considered the establishment of a single Christian religion throughout the world.

Opus maius is not a theological book, but a philosophical one: according to Bacon's intention, it is devoted only to topics that are either common among Christians and non-Christians, or can easily be accepted by non-Christian philosophers. Opus maius consists of seven parts, and the last part, as if crowning the whole building of philosophy, is devoted to moral philosophy, but this moral philosophy is only an introduction to theology, directly based on Revelation. According to Bacon, philosophy shows that "there must be another science outside philosophy, [...] philosophy comes to the discovery of a higher science and claims that it is a science of the Divine."

According to Bacon, moral philosophy, in turn, is divided into four parts: the first justifies the proper behavior of a person in relation to God and angels, the second - in relation to other people, the third - in relation to oneself, and the fourth contains arguments in favor of the Christian faith . The first part, according to Bacon, justifies the existence of God, His omnipotence, infinity, uniqueness, trinity, creation of the world by God, the existence of angels and human souls, the immortality of the soul, Divine providence, death after death, the need for worship of God and moral standards, the need for Revelation, God-manhood of Christ . The second part of moral philosophy, according to Bacon, mainly concerns the dispensation of the family and the state, in the theory of which he largely follows Avicenna. The third part is devoted to personal virtues; in Bacon, her presentation mainly includes citations from ancient authors, primarily Aristotle.

Finally, in the fourth part (in the sense of strongly overlapping with the first), Bacon demonstrates rational arguments in favor of Christianity, which could convince “wise” non-Christians who profess one religion or another (“I could imagine [more] simpler and more crude [than philosophy], the methods of [conversion] of the infidels, corresponding to the bulk of them, but it’s pointless, because the crowd is too imperfect, and therefore the arguments for the faith, designed for the crowd, are rude, primitive and unworthy of the wise. rgumenty, which can judge the sages "). Bacon nevertheless notes that the Christian faith cannot be based only on rational evidence: "one should trust mainly the Church, Scripture, saints and Catholic teachers." However, he is interested in precisely the rational foundations of this trust, which can be accepted by non-Christians. The search for such arguments was a characteristic sign of the era: both Summa against the pagans Thomas Aquinas and the Great Art of Aullius were devoted to this problem.

Bacon examined five major non-Christian religious and ethnic communities (pagans; idolaters; Tatars; Saracens [ie Muslims]; Jews). Many of his comments reveal outstanding for the XIII century. knowledge of other religions and peoples. From the modern point of view, however, it seems that Bacon somewhat overestimated the ease of treatment based on rational arguments, which he posited, perhaps, with excessive haste. For example, Bacon saw one of the arguments for the conversion of Muslims in that "the Saracen philosophers rejected their religious teaching," probably referring to the contradictions between the conclusions of the Arab aristotelians (primarily Avicenna and Averroes) and a number of Islamic dogmas. It should be noted that, firstly, the doctrinal provisions rejected by these thinkers (for example, the eternity of the world and the bodily resurrection of the dead) are common between Islam and Christianity, and secondly, from the historical point of view, the presence of such contradictions led to a crisis not of Islam, and Arab Aristotelianism.

In addition to the religious goal of all sciences, Roger Bacon was also interested in their material fruits, their influence on technology, medicine and other aspects of life, that is, the “practical application” in the modern sense of the word; like his great compatriot and surname Francis Bacon three centuries later, the Franciscan philosopher could also say: “Knowledge is power.” It’s worth mentioning the famous list of technical inventions predicted by Roger Bacon: “navigation tools can be created so that large ships without rowers cross rivers and seas, controlled by one person, and with greater speed than if they were filled with rowers. Wagons can also be created that move without draft animals with unimaginable swiftness [...] flight instruments: so that a person sits in the middle of the instrument, rotating a certain invention, with the help of which [would move], hitting artificially created wings in the air, manners of a flying bird. Also [a small tool can be created] that would lift and lower inconceivable burdens [...] Tools can also be created for traveling under the water of seas and rivers - up to the bottom, and without any bodily danger. [...] And an uncountable number of such can be created, for example, bridges over rivers without supports or any support. " It is interesting that Bacon did not consider all these inventions to be a matter of the future, but of the past: “And [all] it was created in antiquity and, definitely, created in our time, except for an instrument for flight, which I did not see and did not know the person who would see him. But I know a sage who has figured out how to make it. ” Another interesting task that Bacon posed for science is the extension of human life at least until the period that, according to the Bible, the first people lived after the fall (i.e., about a thousand years).

Reasons for Ignorance

Bacon assessed his own era as a time of crisis, decline, degradation: "Now they sin more than in previous times," "corruption is obvious everywhere." This also applies to church education. The "maxims" of Peter Lombard, becoming the main university textbook on theology, took the place of the Holy Scripture, and studying at civil law universities almost completely replaced the study of canonical law. Particularly sharp attacks Bacon subjected the representatives of the Paris school, accusing them of ignorance. The neglect is the study of disciplines, in his opinion, of paramount importance for theology - the grammar of various languages, as well as mathematics. Translations of many important philosophical works and even the Bible are full of errors. Believing in the imminent arrival of the Antichrist, Bacon suspected that he would be armed with powerful weapons, the development of which was blocked in the Christian world due to neglect of the necessary sciences.

The Bacon Encyclopedic Project aims to prevent the spread of these negative phenomena. And therefore it is not surprising that the entire first part of Opus maius is devoted to identifying the main causes of human ignorance and how to deal with it.

Among the main obstacles to comprehending the truth, Bacon calls false authority. It should be noted that criticism of authority really gives Roger Bacon a character that goes somewhat beyond the culture of the Middle Ages, which as a whole was a culture of trust in the book and tradition. It was difficult for medieval people to accept the idea that some kind of information could be simply false; if errors and contradictions were noticed in different sources, they sought to somehow reconcile them by showing in which sense one was true and in another, according to the method of scholastic dialectics, an exemplary application of which was given in the Summa of Thomas Aquinas theology when weighing different " yes ”and“ no ”in resolving each individual issue. It should be noted that in this regard, Roger Bacon appears to be an innovator in methodological theory, but not in practice - the reader of Opus maius is convinced at every step that the credibility of the authorities, including completely false ones, was supported by the Franciscan philosopher. Even in criticizing authority, references to authority are the first argument.

In contrast to the idea of \u200b\u200brejecting authority as a source of knowledge, which was widespread later in the New Age (especially in the Enlightenment), Roger Bacon does not completely refuse to trust authority, declares that all predecessors are worthy of respect, but, nevertheless, he warns against accepting false authority for true and offers to resist false authorities with the help of true, as well as listen to different opinions. Bacon reveals the psychological pathways for the formation of false authorities (following children by parents, students by teachers, subordinates by superiors). According to Bacon, perfect people are even less common among people than perfect numbers among numbers. For each issue, there are many possibilities for deviating from the truth. No one is infallible, except for the authors of the Holy Scripture, therefore it is necessary to study and check the opinions of teachers, examples of which are found in abundance in the history of philosophy. So, the ancients, in their own words, did not know much, people learned a lot afterwards, so followers often correct predecessors, for example, Averroes Avicenna, and that of Aristotle. Even the saints reviewed their opinions, argued and corrected each other. In these arguments, Roger Bacon appears so rare for the Middle Ages and so valuable for the New Age motive for the progress of knowledge: in the future, many things that we don’t know now will become obvious, writes Roger Bacon (with reference to Seneca).

Other obstacles to comprehending the truth are the custom and opinion of the crowd. Custom in this respect is worse than authority, and the opinion of the crowd is even worse; it should not be taken into account at all. In this regard, in the works of Bacon there is a theme of the esotericism of science, which is not at all characteristic of the scientific culture of the New Age, but present in its predecessors - natural philosophers of the Renaissance. The secrets of nature, according to Bacon, should not be revealed to the crowd. From this point of view, his conviction is clear that the unprecedented technical achievements predicted by him have long existed, but are specially hidden and therefore unknown not only to the general public, but also to learned ignoramuses.

Roger Bacon's theory of the causes of ignorance is often seen as anticipating the theory of so-called idols that interfere with the correct knowledge formulated by Francis Bacon. But unlike his namesake, the Franciscan philosopher is not satisfied with the enumeration of the above reasons, but discusses them from a spiritual and ethical point of view, indicating the most important, fourth reason underlying the other three. Such is the concealment of one’s own ignorance under the guise of wisdom, arising from pride. It is because of this reason that many prominent philosophers and theologians have not been recognized for centuries. In criticizing prideful ignorance pretending to be wisdom, Roger Bacon has a Franciscan motive for the superiority of humility and simplicity.

Experienced science

One of the points in which, as is often pointed out, Roger Bacon anticipated the science of the New Age, is the significance of experience in cognition. According to Bacon, an experimental science, firstly, checks the conclusions of all sciences, secondly, provides important facts to other sciences, thirdly, independently explores the secrets of nature, independently of other sciences.

Underlining the meaning of experience is associated with a certain decrease in the value of logical proof, reasoning, and argumentation. Both experience and arguments, according to Bacon, help the knowledge of the truth, but only experience for this in the strict sense is necessary. Not a single one, even the most perfect from a logical point of view, will satisfy a person unless he is directly convinced by experience of the fact being proved. And mathematical proofs are accepted only after an experimental verification - counting in arithmetic, building in geometry.

Like Francis Bacon, Galileo, and later authors of the Enlightenment, emphasizing the role of experience is organically connected with Roger Bacon's criticism of both false authorities and the opinions of the crowd, which are often exposed through experience.

Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to see in Bacon's experience something akin to modern experimental science. It is not a question of conscious interference in the conditions of the phenomenon being studied in order to separate the action of some factors from others, nor about the reproducibility of the results.

With Bacon, experience means everything that a person “experiences” in the broadest sense of the word, direct knowledge “face to face” with reality. It is important to emphasize that this is not only the so-called "sensory experience", perception by the senses. Along with the sensory experience, which he calls external, Bacon also speaks of internal experience. External experience must be supplemented by internal experience in the cognition of visible things, and invisible things are known only by internal experience. Bacon names seven stages of internal experience: 1) purely scientific positions; 2) virtues; 3) the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit listed in Isaiah (wisdom, reason, counsel, strength, knowledge, piety, fear of the Lord, cf. Isa. 11, 2–3); 4) gospel beatitudes (see Matthew 5, 3-12; Luke 6, 20-23); 5) spiritual feelings; 6) fruits that exceed feelings, including the peace of God; 7) admiration of different types (i.e., knowledge of an ecstatic nature). Thus, the "empiricism" of Roger Bacon is closely connected not with sensualism, but with living mystical traditions that are so characteristic of the Middle Ages.

Language Sciences

Medieval Western culture was Hispanic. Even the Greek language was poorly known, including the most educated people. Thomas Aquinas, for example, did not know much Greek and, accordingly, Greek philosophical literature, became acquainted with Aristotle's philosophy in translation, and this circumstance led him to some errors in its interpretation.

Against this background, the words of Roger Bacon about the need to learn languages, and not only Greek, but also Jewish, Arabic, etc., look very relevant for his time. The main reasons he calls for studying them are related to the lack of translations, the low quality of translations, and the fundamental limits of the possibility of translation. Roger Bacon understood that many important terms were missing in the Latin language, making adequate translation difficult. He also understood the fact that the literal translation in many cases is not adequate.

Bacon points out that in Latin there are still no satisfactory translations of many important books, both in philosophy and theology. Among all the literature that, in his opinion, should be “put into scientific circulation” in the Christian West, we note his remark about the need to know the books of the Greek Church Fathers: “if the books of these [authors] were translated, not only would the wisdom of the Latins increase , but the Church would also receive great help against the schism and heresies of the Greeks, for they would be defeated through the utterances of their saints, which they cannot contradict, ”writes Roger Bacon at a time when the necessity of reuniting the eastern and western Churches is recognized ak highly relevant.

Another urgent problem that attracted the attention of Bacon, the solution of which required knowledge of languages, was the problem of errors in the texts. Even the texts of the Bible, which had circulation, were significantly different from one another. This was noticed everywhere, but attempts to make corrections, according to Bacon, often only worsened the situation. Some correctors sought to simplify what they could not understand; others inserted fragments from other translations into the Vulgate text; as a result, the same Greek or Hebrew word was translated differently in different parts of the Bible; still others made corrections following biblical quotes in the writings of the Church Fathers or in liturgical texts, although these quotes for many reasons could in many cases be inaccurate. According to Bacon, the first thing to do was to restore the Jerome text of the Vulgate from the most ancient manuscripts, using the most frequent versions of those available; in cases of discrepancy, it is necessary to check with the Greek or Jewish original. To carry out this work, an authoritative papal commission composed of competent scholars had to be established; her work was to be carried out according to certain principles; corrections made on a private initiative should have been banned. Advancing this program, Roger Bacon was far ahead of his time, laying the foundations of textual criticism of humanists. A revised version of the Vulgate authorized by the Church came out only during the period of the Counter-Reformation.

The activities of Roger Bacon in reforming the education system included not only these advice to the Pope expressed in three Opus. Bacon himself wrote Jewish and Greek grammar. From the first, only a fragment was preserved, from the second - a large part, but only in one copy. Roger Bacon was apparently the only Western author to compose Greek grammar for the Latins. In 1312, the Cathedral of Vienna (possibly influenced by Bacon's arguments) decided to establish schools of Greek and Oriental languages \u200b\u200bin Paris, Oxford and other universities, but these attempts were unsuccessful - only information about temporary teachers who did not have departments was preserved.

With the future humanists, Bacon is associated not only with the awareness of the importance of language learning and the formulation of methodological problems associated with translation and textual criticism, but also with an interest in the principles of rhetorical and poetic reasoning compared to the traditionally studied in logic evidence-based and dialectical reasoning. According to Bacon, rhetorical and poetic arguments are just as important for practical reason as they are for theoretical reason - argumentative and dialectical. But since the practical part of philosophy has an advantage over the theoretical one, special attention should be paid to the study of rhetorical and poetic arguments. These arguments do not meet the standards of scientific rigor to which the arguments of the theoretical sciences must comply; nevertheless, it is practical arguments that can cause faith, sympathy, compassion, joy, love, and corresponding actions in the soul. From here follows their importance for such sciences as theology and canon law. It seems that the arguments leading to the conversion of non-Christians, which Roger Bacon speaks about in the fourth part of his moral philosophy, according to his intention should be assigned to this category.

It should also be noted the important contribution made by R. Bacon to the development of the science of signs. In the Middle Ages, philosophers seriously discussed issues related to the meanings of words. Do words get their meanings naturally or out of human arbitrariness? Does the word “dog” directly refer to a particular dog or the general concept of a dog or the general nature of dogs, and does a specific dog only indirectly? According to Bacon, there are “natural signs” based on the relation of cause and effect (smoke is the sign of fire; trace is the sign of the person who left it) or likeness (statue is the sign of the person she depicts). However, linguistic signs, that is, words, are established by people at their own discretion in order not to mean concepts, but directly real things. On the other hand, each word can be ambiguous: in addition to a specific dog, the word “dog” in a certain context can mean the general nature of dogs, the concept of a dog, and much more. The meanings of words are not rigidly fixed, but are constantly given to them by new speakers in connection with the linguistic and extralinguistic context. The dependence of the meaning of the word on the pragmatic purpose of its use in each particular case, emphasized by Bacon, is quite consistent with his interest in learning and teaching various languages.

Mathematics and Nature Sciences