The marriage of Anna Leopoldovna year. Anna leopoldovna - biography, photos

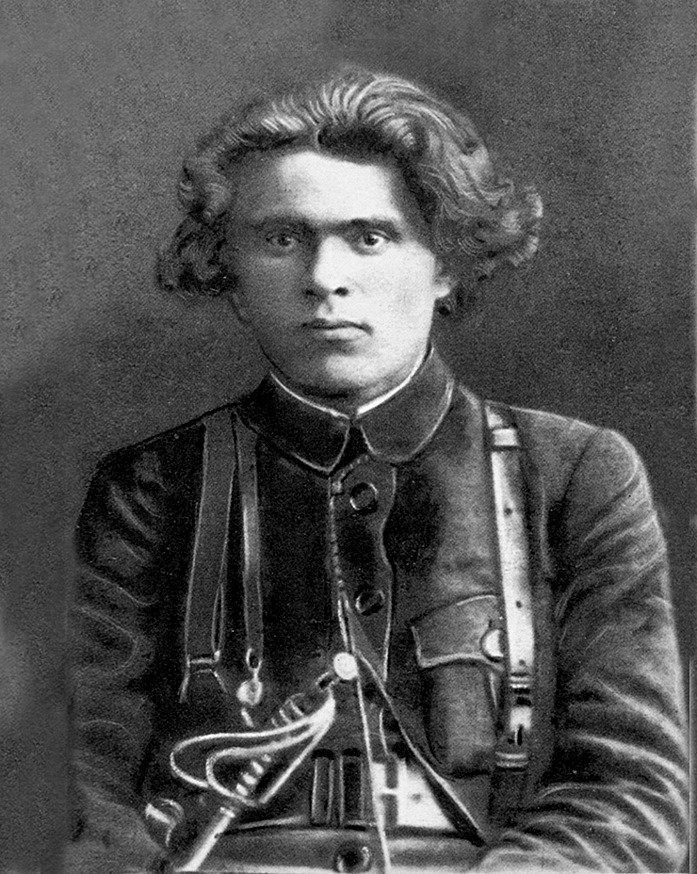

Ruler Anna Leopoldovna, Louis Karawak

- Years of life: December 18 (7th century), December 1718 - March 19 (8th century), 1746

- Years of rule:November 20 (9), 1740 - December 6 (November 25), 1741

- Father and mother: Karl Leopold of Mecklenburg-Schwerinsky and Catherine Ioannovna.

- Spouse: Anton Ulrich of Braunschweig.

- Children: John (), Catherine, Elizabeth, Peter, Alex.

Anna Leopoldovna was the regent of the Russian Empire from November 9 to 25 (November 20 to December 6), 1741.

The childhood and youth of Anna Leopoldovna

Anna's mother was a princess Ekaterina Ioannovnaand his father is the Duke of Karl Leopold of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. At birth, she was called Elizabeth Katarina Christina. Relations between the parents were difficult, the duke treated his wife rudely and fell out of favor with.

In 1722, Ekaterina Ioannovna took her daughter and left her husband, returning to the Russian Empire. They lived under Tsarina Praskovya Fedorovna in Moscow, St. Petersburg and in the vicinity of the capital.

Since 1730, Anna Leopoldovna lived under the Empress. During this period, actively engaged in her education. The widow of General Aderkas became the teacher of Anna Leopoldovna, from 1731 Kondraty Ivanovich Genninger took up her education, Feofan Prokopovich became a mentor in matters of Orthodoxy.

In 1733, Elizabeth Katarina Kristina converted to Orthodoxy and from that moment she became Anna Leopoldovna.

Personal life and family of Anna Leopoldovna

Anna began to look for a suitable party, for this purpose Adjutant General Levenwolde was sent to Europe. His choice fell on the Margrave of Brandenburg Karl, an alliance with which would strengthen relations with Prussia, and Anton-Ulrich Braunschweig, in which case relations with Austria could improve.

In 1733, Anton-Ulrich arrived in St. Petersburg, he attended the solemn rite of the adoption of Orthodoxy by Anna Leopoldovna. It was planned that between Anna and Anton warm feelings would arise, but this did not happen. The girl was indifferent to the groom and did not show any feelings, so they decided to postpone the wedding until she came of age.

But at the same time, Anna began to favor the Count Moritz Karl Linar, the envoy of Saxony in Russia. But the empress planned to marry her to Anton-Ulrich, so Anna Ioannovna, together with E.I. Biron, intervened, and the count was recalled from the Russian Empire.

On July 14, 1739, Anna and Anton-Ulrich got married. A year later, on August 23, their son was born - the future emperor. In October 1740, the empress issued a manifesto, according to which she declared Ivan the heir to the Russian throne, and as regent she chose her favorite Biron.

Anna Leopoldovna - Empress of the Russian Empire

At first, Biron was the regent under Ivan. Prince Anton-Ulrich was unhappy with this and tried to organize a movement against the regent. But the plot was uncovered, as a result of which Anton-Ulrich was forced to abandon all his posts.

Biron was negative and disrespectful to the parents of Ivan VI, even threatened to take the emperor, and send them out of the country. In addition, many did not like Biron, as a result, Christopher Minich, Field Marshal Anna Leopoldovna, with her consent, organized the overthrow of Biron. On the night of November 20 (9), 1740, he, along with a detachment of guards, took into custody Biron, his family and supporters.

After the trial, E.I. Biron and A.P. Bestuzhev was sentenced to death, but regent Anna pardoned them, as a result they were exiled. A manifesto was also issued on the resignation of Biron from his post, as well as on the appointment of Anna Leopoldovna as regent. Her husband, in turn, became the generalissimo of the Russian troops.

Regency Anna Leopoldovna

Anna was practically not interested in public affairs, most of the time she spent reading novels, playing cards and similar entertainments, popular at court. Actual power was in the hands of the Cabinet. A huge role was played by Minich, but gradually he was losing his influence, they began to perceive him as the “new” Biron, in 1741, Minich resigned.

After Minich, Andrei Ivanovich Osterman began to play a large role.

Domestic and foreign policy of Anna Leopoldovna

In March, the ruler established the Commission, which was engaged in state revenues, she was subordinate to the Cabinet of Ministers.

Under Minich, the Russian Empire maintained relations with Prussia; after his resignation, relations with Austria began to improve. Under Anna Leopoldovna, Moritz Karl Linar returned, he became her favorite. He was appointed Chief Chamberlain. Anna Leopoldovna listened to his opinion, Linar actively tried to draw the Russian Empire into the war for the Austrian inheritance.

Prussia and France did not like the rapprochement between the Russian Empire and Prussia, they pushed Sweden to start with it war in 1741

The overthrow and imprisonment of Anna Leopoldovna. last years of life

Supporters of Elizabeth Petrovna planned a conspiracy and wanted to overthrow Ivan VI and his mother from the throne. Lestock, Elizabeth's doctor, spoke with the French envoy Shetardi, who offered help in organizing a coup in exchange for a service. This became known to the British ambassador, who told everything to Osterman. The governor was informed of the attempted conspiracy, Anton-Ulrich and Golovkin tried to convince her to take action. In particular, they talked about the fact that the regent needed to accept the status of the empress, but she was in no hurry and postponed this event to her birthday.

A couple of days before the coup, Anna Leopoldovna called Elizabeth Petrovna to her and asked about her communication with Shetardi and Lestok’s plans. But Elizabeth denied everything, and the regent believed her.

On the night of December 6 (November 25), 1741, Elizaveta Petrovna launched a coup, Anna Leopoldovna, her husband and children were arrested. Anna asked for mercy and did not resist. Elizaveta Petrovna decided to expel the whole family from the country, but when Anna, her husband and children were already in Riga, they were arrested.

There were supporters of the ousted ruler in the state: the Marquis of Bott and Lopukhin discussed the possibility of returning her, chamber footman Turchaninov planned the murder of the empress in order to return power to Ivan VI. Such actions significantly worsened the situation, and at the end of 1742 the family was imprisoned in the Dunamünde fortress.

In January 1744 they were transferred to Ranenburg, and in the middle of summer - to Kholmogory. The Braunschweig family lived in need, the only options for spending time were walking in the park near the house and riding in a carriage for a short distance.

In Kholmogory, Anna Leopoldovna lived until the end of her life. March 19 (8), 1746 she died. Her body was transported to St. Petersburg, where he was solemnly buried in the Annunciation Church of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra.

Family and children of Anna Leopoldovna

Anna Leopoldovna during the marriage with Anton-Ulrich Braunschweigsky gave birth to 5 children:

- John VI (1740 - 1746);

- Catherine (1741 - 1807 gg.);

- Elizabeth (1743 - 1782);

- Petra (1745 - 1798 gg.);

- Alexei (1746 - 1787).

Of all the children, only Ivan VI ruled in the first year of his life.

The fate of this woman is unusually tragic. The granddaughter of Ivan V, Anna Leopoldovna, only for a short moment turned out to be the ruler of the greatest state in the world - Russia. She passed away when she was only twenty-seven years old, and the last thing her eyes saw was the narrow window of a strange house, which had become a prison for her, and a strip of inhospitable northern sky barely visible from the clouds. Such was the result of which the daughter of Peter I, Elizabeth Petrovna, ascended the throne.

Young heiress of John V

Before starting a conversation about who Anna Leopoldovna is in Russian history, it should be clarified what relation she had to the Romanovs' house. It turns out the most direct. It is known that from 1682 to 1696, two sovereigns sat on the Russian throne at once - Peter I and his sibling John V, who had five daughters: Maria, Theodosius, Catherine, Praskovya and Anna. The latter will become empress in 1730 and will reign for ten years. Another daughter of John V, Catherine, is the mother of the heroine of our story - the future ruler, regent, Anna Leopoldovna, who, thus, was a full-fledged representative of the ruling Romanovs' house. Consequently, her son Ivan had all the rights to the throne.

Anna Leopoldovna was born on December 18, 1718 in the small German town of Rostock. Her father was Karl Leopold, Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerinsky, and her mother, as mentioned above, the daughter of the Russian Tsar John V, Tsarevna, the future ruler came to Russia when she was four years old, and here she converted to Orthodoxy. Her mother was the beloved niece of the empress Anna Ioannovna who ruled in those years, and she showed concern for her upbringing, entrusting him to one of the most prominent figures of the Academy of Sciences - Kondraty Ivanovich Genninger. Since 1731, he began to study, but they lasted only four years, since in 1735 a romantic story happened that put an end to his career.

Girl love and forced marriage

The new envoy of Saxony, Count Moritz Karl Linar, arrived in the capital of the empire. This exquisite European handsome man was thirty-three at that time, and the young princess Anna Leopoldovna fell in love with him without a memory. Her mentor Kondraty Ivanovich was in the know and contributed in every way to the development of the novel. Soon there were rumors of a possible wedding. But the trouble is that Anna already had an official bridegroom - the duke Anton Ulrich, whom the empress herself chose for her, guided by state interests. Upon learning of the self-will of the young niece, the Russian autocrat was angry and sent the envoy-seducer out of Russia, and the accomplice of the intrigue, Kondraty Ivanovich, was removed from office. However, the novel did not end there, but more will be discussed about this.

Four years after the events described, the wedding of Anna Leopoldovna with her unloved bridegroom - Anton Ulrich, the Duke of Braunschweig-Luneburg. The celebrations dedicated to this event were distinguished by extraordinary pomp and took place with a huge gathering of people. During the wedding, the parting word was uttered by Archbishop Ambrose (Yushkevich) - a man who was destined to play a crucial role in the religious and political life of the country during the reign of Elizabeth Petrovna. A year later, the young couple had a son, named at the baptism of Ivan.

The end of the reign of Anna Ivanovna

It was the year 1740. In Russian history, he was marked by a number of important events, the main of which was the death of Empress Anna Ioannovna on October 17 (28). In her will, she declared the heir to the throne of the newborn son of Anna Leopoldovna - Ivan, and appointed her favorite Ernst Johann Biron as regent under him. Upon reaching the appropriate age, the young heir was to become the Russian Autocrat John VI.

It should be noted that, as the daughter of Tsar John V, the deceased Empress passionately hated his sibling Peter I and resisted with all her might that any of his descendants take possession of the throne. For this reason, she indicated in her will that in the event of the death of the named heir, the right to the crown passes to the next oldest child of her beloved niece, Anna Leopoldovna. There was no doubt about the candidacy for the post of regent under the infant emperor. It was supposed to be her long-time favorite - Biron.

But fate was pleased to order otherwise. Literally from the first days of his reign, he was faced with stiff opposition, grouped around the parents of a minor heir. There was even a conspiracy to overthrow this unpopular temporary worker. At the head of the attackers was the husband of Anna Leopoldovna - Anton Ulrich. However, they were bad conspirators, and soon their intentions became known to the head of the secret chancellery A. I. Ushakov. This mastermind turned out to be a shrewd man and, foreseeing a possible palace coup, limited himself to only formally “chided” the conspirators.

Deposed Temporal

However, Biron's rule was doomed. On the night of November 9, 1740, the door abruptly opened in the bedroom where the regent and his wife peacefully rested. A group of soldiers entered, led by Field Marshal Christopher Minich, the sworn enemy of Biron and a supporter of Anna Leopoldovna. The former omnipotent favorite, seeing those who entered, realized that this was the end, and, not owning himself from fear, climbed under the bed, being sure that he would be killed. However, he was mistaken. The regent was put in a sled and taken to a guardhouse.

Soon a trial followed, in which Biron was charged with various crimes. Of course, most of them were invented. The sentence was fully consistent with the spirit of the time - a quartering. However, when the poor man was brought to his senses, he heard that a pardon was announced to him, and the execution was replaced by a reference to Pelym, located three thousand miles from St. Petersburg. But during the reign of Empress Elizabeth, the gracious empress transferred him to Yaroslavl, and eventually Peter III, summoning Biron to the capital, returned all orders and insignia to him. A few years later, Catherine II restored the former regent in the rights to the duchy of Courland that once belonged to him.

The rise to power and the emergence of a dangerous favorite

So, the hated temporary worker was expelled from the palace, and state rule passed into the hands of the mother of the heir to the throne. Anna Leopoldovna became the regent. The Romanovs, leading their kind along the line of Tsar John V, were temporarily at the top of Russia's state power. At the very beginning of the next 1741, a joyful event occurred in the life of a young woman: the newly appointed Saxon envoy Karl Linar arrived in Petersburg - her former love, which had not had time to cool down. Accepted by Anna Leopoldovna immediately, he immediately became her favorite.

Since the ruler was married, in their relationship they had to observe certain propriety. Linar settled in a house near the Summer Garden, where Anna lived in the Summer Palace at that time. To provide a sufficient excuse for his presence in the palace, she appointed a lover as Oberkamerger. Soon, the highest mercy extended to the fact that the favorite was awarded two highest Russian orders - Andrew the First-Called and Alexander Nevsky. For what merits he received them, the courtiers could only guess.

Soon, however, Anna Leopoldovna allowed her lover to intervene in serious state affairs and did not make any decisions without consulting him. With her connivance, Linar became a key figure in the struggle of the court parties, eager to drag Russia into the war for the Austrian inheritance. In those years, a number of European states tried, by declaring the will of the Austrian emperor Charles VI illegitimate, to take possession of the property of the Habsburg house in Europe. This behavior of the Saxon envoy caused discontent among the highest dignitaries, who feared the appearance of a new Biron in his person.

Separation from Linar

In order to somehow veil the connection that was taking on a scandalous turn, Anna Leopoldovna (the empress, after all) was forced to go to tricks, which, however, could not mislead anyone. So, for example, in the summer of 1741 she betrothed Linar to her maid of honor and her closest friend Baroness Juliana Mengden. But, becoming a bridegroom, he, nevertheless, could not officially enter the Russian service, since he remained a subject of Saxony. To get the necessary permission, in November of that year, Linar left for Dresden.

Before leaving, he, as a visionary man, warned Anna Leopoldovna about a possible attempt to seize power by the supporters of the daughter of Peter I Elizabeth Petrovna. However, he was going to return soon and take everything under his control. When parting, they did not know that they were saying goodbye forever. When, having received the desired permission from the government of Saxony, Linar returned to Petersburg in November of the same year, he was awaited in Konigsberg about the arrest of Anna Leopoldovna and the accession to the throne of Elizabeth Petrovna. His worst fears came true ...

Peter's daughter at the head of the guard

The palace coup occurred on the night of November 25 (December 6), 1741. In those days, the main political force was the guard created by Peter the Great. Able to ascend to the throne and overthrow from it, she already felt her strength in February 1725. Then the widow of Peter I, Empress Catherine I, came to power on her bayonets. Now, taking advantage of the fact that Anna Leopoldovna, whose rule provoked general discontent, underestimated the strength of the guard, Elizabeth managed to win over the Preobrazhensky Regiment in St. Petersburg.

On that fateful night for the Russian ruler, the 31-year-old beauty Elizaveta Petrovna, accompanied by three hundred and eight grenadiers, appeared in the Winter Palace. Not meeting any resistance anywhere, they reached the bedroom, where Anna Leopoldovna and her husband rested peacefully. To the death of the frightened regent, her deposition and arrest were announced. Witnesses of this scene subsequently said that Elizabeth, whispering in her arms the one-year-old heir to the throne, who was in the same room and woke up from the sudden noise, quietly whispered: “Unhappy child.” She knew what she was saying.

The Way of the Cross yesterday

So, the Braunschweig family was arrested, including Anna Leopoldovna. Empress Elizabeth was not a cruel person. It is known that at first she planned to send her captives to Europe and limit herself to that - at least it was said in the manifesto by which she declared herself empress. The failed Queen Anna Leopoldovna and her family were temporarily sent to Riga Castle, where she spent a whole year waiting for the promised freedom. But suddenly, the plans of the new mistress of the Winter Palace changed. The fact is that a conspiracy was discovered in St. Petersburg, the purpose of which was the overthrow of Elizabeth and the release of the legitimate heir Ivan Antonovich.

It became obvious that the Braunschweig family will continue to be a banner for all kinds of conspirators, thereby presenting a known danger. The fate of Anna Leopoldovna was decided. In 1742, the prisoners were transferred to the Dunamünde fortress (near Riga), and two years later to the Renenburg fortress, located in the Ryazan province. But here they did not stay long. Within a few months, the highest decree came to lead them to Arkhangelsk for further detention in the Solovetsky Monastery. In the autumn thaw, under heavy rains, Anna Leopoldovna and her unhappy family were sent north.

But that year, early frosts and ice hummocks ruled out any possibility of crossing to Solovki. The prisoners were settled in Kholmogory, in the house of the local bishop, and vigilantly guarded, excluding any possibility of communication with the outside world. Here they forever said goodbye to their heir son. Ivan Antonovich was isolated from them and placed in another part of the building, and subsequently his parents did not have any news of him. For greater conspiracy, the young ex-emperor was ordered to call a fictitious name Gregory.

Death and Belated Honors

Recent years, full of grief and tribulation, have undermined the health of a young woman. The former regent and sovereign ruler of Russia died in captivity on March 8 (19), 1746. The official cause of death was declared or, as they used to say in the old days, a “fireworm”. While under arrest, but not separated from her husband, Anna gave birth four more times to children, information about which has not been preserved.

However, the story of Anna Leopoldovna did not end there. Her body was transported to the capital and with great solemnity interred in the necropolis of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra. The funeral was held according to all the rules provided for by the rules for the burial of persons belonging to the reigning house. Since then, Anna Leopoldovna is necessarily mentioned in the official lists of the rulers of the Russian state. The Romanovs were always jealous of respecting the memory of members of their surname, even those whose deaths themselves were involved.

The Iron Mask of Russian History

The fate of Ivan, the heir to the throne, which was born by Anna Leopoldovna, was especially tragic. His biography was formed in such a way that gave historians an occasion to call him the Russian version of the Iron Mask. Immediately after the seizure of power, Elizabeth took all possible steps so that the name of the heir to the throne overthrown by her would be forgotten. Coins with his image were withdrawn from circulation, documents mentioning his name were destroyed, and any memories of him were banned under pain of harsh punishment.

Having seized power by means of a palace coup, she was afraid of the possibility of herself becoming a victim of another conspiracy. For this reason, in 1756, she ordered a fifteen-year-old prisoner to be brought in and kept unhappy in solitary confinement. There, the young man was even deprived of his new name, Gregory, and was only mentioned as a “famous prisoner." Strictly forbidden his contact with others. This requirement was so strictly observed that during all the years of imprisonment the prisoner did not see a single human face. Not surprisingly, over time, he showed signs of mental distress.

The highest visit to the prisoner and fast death

When the new empress, Catherine II, who also seized power with the support of the guard, replaced Elizaveta Petrovna, she, in order to give her rule more legitimacy, thought about the possibility of marriage with the legitimate heir Ivan who was in the fortress. To this end, she visited him in the Shlisselburg casemate. However, when she saw the degree of physical and mental degradation that Ivan had achieved during the years of solitary confinement, she realized that there was no question of marriage with him. By the way, the empress noted that the prisoner is aware of his royal origin, that he is literate and wants to end his life in the monastery.

The reign of Catherine II was by no means cloudless, and during the time of Ivan's stay in the fortress, several coup attempts were made to elevate him to the throne. To stop them, the empress ordered the prisoner to be killed immediately if there was a real threat of his release. And in 1764, this situation developed. Another conspiracy arose in the ranks of the garrison of the Schlisselburg fortress itself. Led by his second lieutenant V. Ya. Mirovich. However, the internal security of the casemates fulfilled their duty: Ivan Antonovich was stabbed with their bayonets. Death interrupted his short and tragic life on July 5 (16), 1764.

Thus ended these sons of the reigning Romanov dynasty - the rightful heir to the throne, John VI and his mother Anna Leopoldovna, whose brief biography served as the topic of our conversation. Not all Russian rulers were destined to die a natural death. The ruthless, unchecked struggle for power sometimes resulted in tragedies like the one we were recalling now. The years of the reign of Anna Leopoldovna entered the history of Russia as part of a period called the “Age of the Temporary Workers”.

Posted by TimOlya. This is a quote from this post.

The exiled queen Anna Leopoldovna. Part 2. The Fair Queen

Johann Heinrich Wedekind

Nevsky Prospect. St. Petersburg.

Most of the dreams of the young princess were dispelled immediately. Petersburg turned out to be a brilliant, but damp, cold and uncomfortable city for living, hastily built on stilts and “on bones”. It was difficult to call Anna Ioannovna an affectionate, loving and generous relative ...

Empress Anna Ioannovna

As for the adventures, the first and main adventure turned out to be when the suspicious Biron ordered the seized, paranoid suspect, taken to the Secret Chancellery and tortured to death one of the maids of honor accompanying Anna Leopoldovna.

Portrait of the Duke of Courland E.I. Biron. Rundale Palace.

It is not known what he really wanted from the girl ... But Anna Leopoldovna was in utter shock and even became ill with emotions: she was very afraid for the adored Julia! Anna tried not to part with her even for a moment - even at night she laid her in her bedroom - as she hoped that the girl would certainly not be torn out of her arms.

Anna Leopoldovna

In 1739, Anna Leopoldovna was married to Anton-Ulrich Braunschweig-Lunenburg. But even then, Julia Mengden had such complete control over the mind and heart of the princess that she even ordered when young spouses should spend the night together, and when not. Actually, Anna Leopoldovna lived with her husband only six days a month, and only for the sake of the birth of an heir. Moreover, according to the recollections of eyewitnesses, whenever Julia let Anton Ulrich into her bedchamber, the princess began to sob hysterically and Julia had to comfort her with kisses and gentle words for a long time.

Anna Leopoldovna and Anton-Ulrich Braunschweig-Lunenburg

Anna Leopoldovna

Anton-Ulrich Braunschweig-Lunenburg

It is clear that, above all, the young husband was not enthusiastic about the situation. Anyway, few at the court understood the strange relations of Anna Leopoldovna and Julia Mengden. And Anna Ioannovna herself suspected her niece and her maid of honor in unnatural inclinations. True, in those days, and even more so in Russia, they had a very rough idea of \u200b\u200bwhat lesbianism was. So approximate that it was even believed that one of a pair of lesbians must certainly be something hermaphodite water, that is, have the beginnings of the male genital organs. Since Anna Leopoldovna did not have them for sure, because the princess was examined by a doctor before the wedding, in order to sort out her suspicions, the empress ordered an examination of Julia Mengden ... who, of course, showed that Julia is a normal woman physically, besides but also a girl.

Grand Duchess Anna Leopoldovna at birth Elizabeth Katarina Christina, Princess of Mecklenburg-Schwerinsk

Louis Caravac

Here is how, after many years, the diplomat Mardelfeld wrote about it: “I am not surprised that the public, not knowing the reasons for the princess’s supernatural attachment to Julia, accuses this girl of being addicted to the tastes of the famous Sappho; but I can’t forgive the Marquise Bott, blessed by the Grand Duchess, that he attributes the princess’s tendency to Julia to be the last woman with all the qualities necessary for this ... This is black slander, since the late empress, because of such accusations, ordered to carefully examine this girl, and the commission that performed it reported that she had found her a real girl without the slightest male sign. ”

Grand Duchess Anna Leopoldovna at birth Elizabeth Katarina Christina, Princess of Mecklenburg-Schwerinsk

Louis Caravac

Grand Duchess Anna Leopoldovna at birth Elizabeth Katarina Christina, Princess of Mecklenburg-Schwerinsk

Louis Caravac

Grand Duchess Anna Leopoldovna at birth Elizabeth Katarina Christina, Princess of Mecklenburg-Schwerinsk

Louis Caravac

Now it’s not clear what it was: a really love affair, or just an ardent sentimental friendship, very common in the XVIII century, and in the XIX century, and even at the beginning of the XX.

As for tears on the threshold of the matrimonial bedroom: maybe Anton-Ulrich was not a very experienced lover, and could not give his wife bodily joys?

Anton Ulrich of Braunschweig

Anton Ulrich of Braunschweig

Anton-Ulrich was a short-sighted man and also meek, so that he eventually came to terms with the rules established by Julia for his visits to the conjugal bedroom. In addition, the dog hunting and training of soldiers interested him much more than proximity with his wife. And very soon, he, like Anna Leopoldovna herself, was inclined to believe that the fulfillment of marital duties was necessary only for the sake of extension of the clan. They even said that they did not talk to each other at all. But their children were born regularly. In 1740, Ivan, in 1741, Catherine, in 1743, Elizabeth, in 1744, Peter, in 1746, Alexei ...

Emperor Ivan Antonovich in the cradle. Engraving by I. Leopold. 1740

However, the last three children were born already in custody.

And before, Anna Leopoldovna was to reign with her young son Ivan for a year and a half.

Empress Anna Ioannovna died in October 1740. Before that, she had suffered from gout for many years, and in recent years she had manifested a hidden, evil “stone” disease, which caused the death of the Empress, who did not reach forty-seven years. The memoirist wrote that upon opening the empress’s body “they found in her loins a stone of such a size that he embraced the entire inside of the womb and completely disfigured the structure of it”. That sounds fantastic. Events developed so that at noon on October 6, having sat down for dinner with Biron and his wife, the empress felt lightheaded and lost consciousness.

Valery Ivanovich Jacobi (1834-1902) fragment of the painting "Jesters at the Court of Empress Anna Ioannovna"

The duke was bewildered. In confusion, he sent people to Osterman, as well - to call Minich and several other close dignitaries. I met them in tears and lamented: I lamented about my future and, of course, Russia. To this Minister Cherkassky immediately said to Biron: “I do not know anyone more capable and worthy of your lordship to rule the state ...”and continued in the same vein. The rest, without hesitation, joined. It was not difficult for them to realize that if the empress came to her senses even for a short while, those who dared to challenge the proposal made to the duke would find themselves first in a dungeon, and then, possibly, on a scaffold. It was decided to gather as soon as possible the council of all the first persons of the state.

Biron immediately added that it was necessary to transfer the Russian throne to the two-month-old prince, baby John, the son of Anna Leopoldovna and Anton-Ulrich of Braunschweig. The childless empress treated him with tenderness, like a grandson.

Emperor Ivan Antonovich. Unknown artist.

... The Duke Biron immediately sent several gentlemen urgently summoned to the palace to Chancellor Osterman, who did not leave his house due to illness. Under his leadership, this company was to compose a manifesto declaring the two-month-old John Antonovich the future emperor John VI - the rightful heir to the Romanov throne. By the time the empress, having regained consciousness, gained capacity and clarity of thought, the manifesto was ready; Biron entered her, she signed. The manifesto proceeded from Anna Ioannovna, as it was supposed, to the palace church, filled with a meeting of the first persons of the state, raised by alarm, and all ranks swore to the unexpectedly acquired heir to the throne. The sworn and guards, built on the square in the form of the palace. It was the turn of the inhabitants of St. Petersburg. Separately, the Empress, by her decree, was to command the Duke of Biron, in the event of her death, to be regent with the baby and rule Russia until the age of John VI. Then she straightened up a little, as she was not going to die immediately. Putting the papers under the head of her bed, she said to the duke: “I will consider” ...

Andrey Ivanovich Osterman.

Everyone was excited. Biron and the ministers even tried to persuade Princess Anna to go to her aunt and convince her to entrust the administration of the state under John to the duke. Their request looked rather strange, as if nobody had put Anna Leopoldovna herself.

Having finally called Osterman to herself, the Empress signed everything, for it became clear to her that the end was near. In the evening of October 17, she said goodbye to everyone, the church forgave her sins. Upon completion of the proper rites, Anna Ioannovna ceased to exist on earth.

At night, the guards increased.

The next morning, the Life Guards and army regiments listened to the regency decree on Palace Square.

Emperor John Antonovich. Ruler Duke Ernest Biron. Ruler Anna Leopoldovna. 1740-1741

The baby was transferred to the winter palace, and Biron agreed that John's parents would also move there. Not even a week had passed after the death of the empress, before Biron had been informed of a murmur against him. Two guards officers and a cabinet secretary were taken into custody, they were tortured. The streets of St. Petersburg were filled with guards and horse rides. Headphones and scammers scurried about everywhere. Every day, people of any rank were dragged into the Secret Chancellery, who inadvertently discussed the position of the authorities.

Grand Duchess Anna Leopoldovna at birth Elizabeth Katarina Christina, Princess of Mecklenburg-Schwerinsk

Having come to the Minister, Prince Cherkassky, some of the nobles talked about how to get rid of the hated regent and transfer the reins to Princess Anna Leopoldovna, who now became the Grand Duchess, and her husband was promoted to generalissimo. On November 8, before noon, Field Marshal Minich came to Anna Leopoldovna to pay homage and at the same time outlined to her the danger posed by Biron. He immediately received the approval of his plan to overthrow the temporary worker. In the evening, Minich and his daughter-in-law dined at Biron. In the middle of the night, the field marshal with his adjutant Manstein took three officers and eighty grenadiers. With this escort he went to the summer palace, where the body of Anna Ioannovna was exhibited and where the duke Biron lived. In the guard there were three hundred guardsmen personally subordinate to Field Marshal Minikh Preobrazhensky Regiment. The guards did not mind the action. The adjutant with twenty grenadiers broke into the room where Biron rested with his wife. He tried to hide under the bed and Manstein pulled him by the leg, the soldiers twisted him, and shut his mouth with a handkerchief, threw a rough overcoat on his shoulders - underwear, dragged him out of the palace and pushed him into the carriage.

Count Burkhard Christoph von Münnich (in Russia was known as Christofor Antonovich Minikh; May 9, 1683, Neuenhuntorf, Oldenburg - October 16 (27), 1767, St. Petersburg) - Russian Field Marshal (1732), whose most active period of activity fell on reign of Anna Ioannovna, lieutenant colonel of the Preobrazhensky Life Guards Regiment (from 1739 for the victory over Turkey)

It had not yet dawned when crowds of people surrounded the winter palace, noisily greeting the happy event. Under cannon fire, the new Grand Duchess Anna Leopoldovna took the oath of all the noblest ranks and became ruler under John VI. The people again kissed the cross in the churches. This time to the Braunschweig house.

Grand Duchess Anna Leopoldovna at birth Elizabeth Katarina Christina, Princess of Mecklenburg-Schwerinsk

Emperor Ivan Antonovich with his mother, Princess Anna Leopoldovna. Unknown artist. XVIII century

Tsarina Anna Leopoldovna was useless. Political decisions for her were made by Minikh, and she herself was still interested only in novels, Julia and children (shortly after her accession to the throne, she became pregnant and her daughter Catherine was born).

Grand Duchess Anna Leopoldovna at birth Elizabeth Katarina Christina, Princess of Mecklenburg-Schwerinsk

Having transformed from the favorite of the princess to the favorite of the regent, Julia Mengden gained absolutely unlimited power. Everyone, both courtiers and ambassadors of foreign powers, knew that in order to achieve something from Anna Leopoldovna, one must first turn to Julia Mengden. Even the Orthodox clergy had to bow to the favorite!

Emperor Ivan Antonovich

Emperor Ivan Antonovich

Emperor Ivan Antonovich

Emperor Ivan Antonovich with maid of honor Julia von Mengden. Unknown artist. 1740-1741

The brief reign of Anna Leopoldovna ended just as casually, absurdly and swiftly as it began.

On the advice of Minikh, Anna Leopoldovna intended to imprison her cousin, the daughter of Peter the Great, the beautiful Elizabeth.

Minikh feared that Elizabeth, who was called the “spark of Peter the Great”, beloved by the troops, people and the majority of the Russian nobility, could create a conspiracy and overthrow the Germans disgusted by all, and decided to warn this ... Not knowing that the Transfiguration, loyal to Peter, had already been drawn up. ready to support his daughter and on her bayonets to raise her to the throne.

Equestrian portrait of Elizabeth Petrovna with arachnochka.

Georg Christopher Grotto

So the decision of Anna Leopoldovna regarding the arrest of Elizabeth and her imprisonment in the monastery, which was immediately reported to Elizabeth, only accelerated the fall of Minich and the death of the Baunschweig family.

Years of life : December 7th 718 - March 7, 1746 .

Years of regency (board): November 9, 1740 - December 25, 1741.

The ruler of the Russian Empire (from November 9, 1740 to November 25, 1741), the daughter of the Duke Karl-Leopold of Mecklenburg-Schwerinsky and Tsarevna Ekaterina Ioannovna. Born in Rostock on December 7, 1718; there she was baptized according to the rite of the Protestant church and was named Elizabeth-Christina. At home, she lived only up to three years. The conjugal life of her mother, Ekaterina Ioannovna, was very unhappy: the rudeness, grumpiness and despotism of her husband were completely unbearable. She still lived with him for six years, but could no longer tolerate his antics and left for Russia (1722), taking her daughter with her. In Russia they were met unfriendly. She lived with the old Queen Praskovye Feodorovna, now in Moscow, then in Petersburg, then in the vicinity of the capitals.

Elizabeth-Christina grew up in a dark environment, under the supervision of a poorly educated mother, without getting the right upbringing and education. Circumstances changed in 1731. The accession to the throne of Anna Ioannovna, who had no children, raised the question of her successor. Wanting to keep the Russian throne behind her family, Empress Anna brought the 13-year-old niece closer to her court and surrounded her with a staff of ministers and mentors. The Frenchwoman, the widow of General Aderkas, was appointed the teacher of the princess; in Orthodoxy it was taught by Feofan Prokopovich himself. However, under the guidance of these persons, the spiritual development of the princess moved little forward; they did not instill in her either mental and moral interests, nor even a taste for a cultural society and the ability to keep themselves with dignity in it. However, she learned the French and German languages \u200b\u200band got used to reading. To find a suitable bridegroom, Adjutant General Levenwold was sent to the West, who proposed two candidates: Margrave of Brandenburg Karl and Prince Anton-Ulrich of Braunschweig-Bevern-Luneburg. Marriage with the first would lead to rapprochement with Pussia, marriage with the second, nephew of Emperor Charles VI, with Austria. The Vienna court made every effort to upset the marriage with Margrave Karl and, relying on the sympathy of the leaders of Russian politics, who favored Austria, ensured that Anton-Ulrich was allowed to come to Russia. On January 28, 1733, he arrived in St. Petersburg, was accepted into the Russian service, and on May 12, 1733 was present at the solemn ceremony of the adoption of Orthodoxy by Princess Elizabeth.

Her new name, given in honor of the Empress, was Anna Leopoldovna. But they were not in a hurry with the marriage, the coldness shown by Anna Leopoldovna to the groom was too obvious, and the wedding was postponed until the bride came of age. Anna’s indifference to the groom was supported and strengthened by Anna’s passion for the Saxon envoy, Count K.M. Linar, handsome and dandy. This passion was patronized by Ms. Aderkas, a supporter of the Prussian party. The angry empress ordered to send Aderkas abroad (1735), and Count Linar, at her request, was recalled by his court. Strict supervision was established for Anna, her life became even more isolated and monotonous than before: strangers came to her only on official visits, on special days. Anna Leopoldovna still led an empty and idle lifestyle, and if she read, then only works of French fiction. So she lived four years before marriage (1739). He was accelerated by the fact that Biron planned to marry his son Peter to Anna Leopoldovna. Rejecting Biron's offer, Anna expressed consent to marry Anton-Ulrich, and the marriage was celebrated on July 3, 1739. Biron hated the newlyweds and spoiled their lives as much as they could. Anna’s family situation was just as bad as her mother’s. She did not love her husband, quarrels between them were frequent; mutual enmity was fanned by the court.

On August 12, 1740, Anna had a son, named at baptism, in honor of his great-grandfather, John, and declared the manifesto on October 5, 1740, heir to the throne. On October 17, 1740, Empress Anna Ioannovna died, and Biron became regent of the empire. During the lifetime of the emperor’s parents, the Biron regency was a strange and offensive phenomenon for them, which many in Russia spoke openly. In the regency clause itself there were points that were supposed to cause Biron's clashes with the other first persons of the court and with the emperor's parents; such were the questions about the rank of generalissimo, about the money for maintaining courtyards, etc. Biron did not know how or did not want to avoid clashes with the prince and princess, but he thought to suppress the displeasure among the wider sections of the population with strict measures. The general enmity towards Biron did not bring the prince closer to the princess; Anna did not support her husband, clearly offended by Biron. The regent heard rumors of unfavorable conversations at the princess’s court. Her secretary, Semenov, openly doubted the authenticity of the empress’s signature on the regency decree. Biron was indignant and threatened Anna in anger that he would send her and her husband to Austria, and he would call Prince Golshtinsky to Russia. At the same time, he intended to transform the guards: identify ordinary soldiers from the noblemen into army regiments with officers and replace them with commoners. Rumors about it and Biron’s gross threats frightened and alarmed Anna. She turned to Minich for advice, who, with her approval, drew up and implemented the deposition plan of Biron. On the night of November 8 to 9, he, accompanied by a small detachment of soldiers, arrested the regent. His relatives and devotees suffered the same fate. A court was ordered over those arrested, who sentenced Biron and Bestuzhev to death by quartering, but, pardoned by the ruler, they were exiled: the first to Pelym, the second to his villages.

On November 9, a manifesto was announced on the appointment of the ruler of the state, instead of Biron, Anna, with the title of Grand Duchess and Imperial Highness. On the occasion of this event, favors were declared to the people and many returned to Siberia by the previous government were returned. The first dignitary of the state was Minich, but not for long. Arranging a coup, the ambitious Minich dreamed of primacy in the state and the rank of generalissimo, but by decree on November 11 this rank was given to Prince Anton, however, with the proviso that this was a concession from the side of Minich. But Minich was singled out as a nobleman, and although Osterman was granted the rank of Admiral, Cherkassky as the Grand Chancellor, Golovkin as the Cabinet Minister and Vice Chancellor, however, Minich was declared "the first in the empire" after Prince Anton and became chief executive as internal , and the country's foreign policy. This position of Minich, especially undesirable for Osterman, was inconvenient for many. Between the ministers began a dull struggle; there was no unity in management. Already in early January 1741, the enemies of Minich achieved the fact that in military affairs he was subordinated to Prince Anton, and in foreign policy to Osterman.

On January 28, 1741, the Cabinet was divided into three departments: military affairs, led by Minikh, external and naval, led by Osterman, and internal with Cherkassky and Golovkin. Only the land army, irregular troops, artillery, fortification, the cadet corps and the Ladoga Canal remained under the jurisdiction of Minich, and even then he had to report to the prince about everything. Finally, Anna stopped taking Minich for a private report in private, and always called for the reception at the reception. Offended Minich demanded the resignation, which was given to him (March 3, 1741) in a very offensive environment for his pride. The elimination of Minich was primarily reflected in the foreign policy of Russia: previously favorable for Prussia, it now leaned on the side of Austria. The imperial ambassador who left Russia during the lifetime of Empress Anna Ioannovna, the Marquis of Bott, returned to Petersburg; Linar also returned. They easily managed to attract Russia to their old ally, Austria, and to achieve the promise of a 30- or 40-thousandth auxiliary corps. Linar succeeded in matters not only political, but also personal; they showered him with favors - they made him the chamberlain of the Russian court, granted the orders of Alexander Nevsky and Andrew the First-Called and, to finally bind him to Russia, decided to arrange his marriage with the favorite of the ruler, Juliana Mengden. Linar left for his homeland to prepare everything necessary for marriage and moving to Russia, but on the way back, in Koenigsberg, he learned about the fall of the government of Anna Leopoldovna. The appearance of Linar in Russia and his role at court reminded courtiers of the Biron era: many were unhappy with the new favorite, and Prince Anton in particular. Disagreements between the spouses intensified and contributed to the fragmentation of the already unfriendly government on the party. The first time after the fall of Minich, Osterman dominated; he found support from Prince Anton. His opponents were Golovkin, who found sympathy and help from Yu. Mengden and the ruler herself, who often managed the affairs entrusted to Osterman without even informing him of that. The discord in the government gave his activity a casual and erratic character.

The internal activities of Anna's government concerned administration, justice, finance, and industry. So, to relieve the red tape of petitioners, the post of re-master (November 12, 1740) was established on the Highest Name, who, in addition to receiving, analyzing and sending petitions, announced to the Senate the highest resolutions on his comprehensive reports and the Synod - personal orders. This post was soon abolished (March 4, 1741), and its conduct was transferred to the Cabinet. Attention was drawn to the slow progress in the Cabinet and the Senate, and measures were taken to accelerate them. To streamline finances, it was proposed to revise all items of income and expense, reducing, as far as possible, the latter. All government seats were charged with the obligation to send to the Cabinet statements of their available money. Each department was required from year to year to retain a known balance from its sums (January 12, 1741). In March 1741, a special "commission for the consideration of state revenues" was established, subordinate to the supervision of the Cabinet. In order to regulate trade and industry, a bankruptcy charter was issued (December 15, 1740) and "regulations or working regulations for cloth and carp plants" (September 2, 1741), which concerned monitoring the maintenance of machinery, the size and quality of cloth, as well as attitudes of entrepreneurs to workers (15-hour working day, minimum wages, hospitals for workers, etc.). But not domestic, but foreign policy attracted mainly the attention of the government. The rapprochement between Russia and Austria was undesirable not only for Prussia, but also for France, which, in the end, managed to incite Sweden to declare war on Russia (June 28, 1741). This unsuccessful war for Sweden ended already in the reign of Elizabeth by the Abos peace. Starting the war, the Swedes declared a manifesto addressed to the Russians, declaring themselves defenders of the rights to the Russian throne, Elizabeth and Peter, Duke of Holstein.

In St. Petersburg, even before the war, the Swedish envoy Nolken and the French ambassador Shetardi intrigued with the goal of elevating the crown princess Elisabeth to the throne, convincing her to cede the Swedish Russian Baltic lands in gratitude for military assistance. Shetardi communicated with the prince both personally and through Lestock, but did not achieve a definite answer. Elizabeth understood well that her main support was not the Swedes and the French, but the guard. The intrigues of Shetardi and his minions were rather awkward and were not a secret for the Russian court. The English ambassador told Osterman in detail about them. The Chancellor reported that ruler, but neither his ideas, nor the convictions of Botta and Prince Anton-Ulrich prompted her to take decisive measures against the supporters of the princess. Golovkin advised, in order to stop all attempts to overthrow the ruler, to accept her the title of empress, but she put off this until her birthday, December 7, 1741. In general, Anna was very unsuitable for the role that fell to her lot: uneducated, lazy, careless, she did not want and did not know how to delve into state affairs, but on the other hand, she intervened in the government of the country and wanted to manage it. By spinelessness, she succumbed to the influence of the people around her, whose choice she was completely unable to. Her favorite pastime was a card game, her favorite society was a circle of people very close to her, with Mengden at the head. They sometimes met at her place in the morning, and Anna Leopoldovna went out to them directly from the bedroom, without dressing up, without even washing, without combing her hair, and spent the whole day with them like that until the evening, chatting and playing. With her characteristic good-natured frivolity, she accepted the news of the plans of the princess. Only on November 23, at the kurtag in the Winter Palace, the ruler decided to explain to the princess about her relations with Shetardi and about the activities of Lestock, threatening to take measures against them. On November 24, the guard received an order to speak to Vyborg. Prince Anton-Ulrich wanted to arrest Lestock and place pickets in the streets, but Anna did not agree to this. A conversation with the ruler and an order on the appearance of the guard prompted the prince to activity. On the night of November 24 to 25, she, accompanied by a detachment of guards, arrested the ruler, her husband, a young emperor and his sister, Catherine (born July 26, 1741). Tsesarevna personally entered the chambers of the ruler and woke her. Anna Leopoldovna did not resist the coup, but merely requested that neither her children nor Juliana Mengden do harm. Elizabeth reassured her, promised to fulfill her request, and in her sleigh took her to her palace, where the ruler’s family was brought. On the same night, Minich, Osterman, Levenwold, Golovkin, Mengden, Lopukhin were arrested. In a manifesto on November 27, 1741, announcing the abolition of the government of Emperor John VI, the whole Braunschweig family was announced that the empress, "at least not cause them any grief," sends them abroad.

On December 12, 1741, Anna and her family went to Riga, where, however, they were detained and held until December 13, 1742. The deposed dynasty turned out to be active enemies and friends; the former were stronger than the latter. The Prussian envoy, on behalf of his king, and Shetardi, personally on his own behalf, was advised to send the Braunschweig surname inland. The Marquis of Bott and the Lopukhins intrigued (confining themselves to chatter) in favor of the deposed government. But there were also more resolute supporters of Anna: the chamber footman Turchaninov plotted regicide in order to free the throne for John VI. All this worsened the situation of the family of the former ruler. In December 1742, she was imprisoned in the Dunamünde fortress, where Anna had a daughter, Elizabeth. In January 1744 they were all transported to the city of Ranenburg (Ryazan province), where Julian Mengden and the adjutant of Prince Anton-Ulrich, Colonel Gameburg, arrived. In July of the same 1744, Baron Korf arrived in Ranenburg with the order of the empress to transport the Braunschweig family first to Arkhangelsk and then to Solovki. The former ruler went on a long and difficult journey, sick, in the autumn thaw. Her suffering was aggravated by the fact that Julian Mengden, along with Colonel Geimburg, was left in Ranenburg under heavy guard. The Braunschweig surname could not reach Solovki; the ice prevented it and left it in Kholmogory, placing it in a former bishop's house surrounded by a high tyne, under the watchful supervision of the watchmen, who completely separated it from the outside world. The prisoners' entertainment was walking in the garden at the house and riding in a carriage, but not further than two hundred fathoms from the house, and then accompanied by soldiers. Prisoners, due to the insignificance of funds allocated for their maintenance, and the arbitrariness of the guard, often needed the most necessary for their existence. Their life was very hard. Under such conditions, Anna Leopoldovna gave birth to the sons Peter (March 19, 1745) and Alex (February 27, 1746). Having given birth to the latter, Anna fell ill with a maternal fever and died at the age of 28.

On March 7, 1746, Guryev, who replaced Korf in the Kholmogory Mountains, sent, according to this instruction, the body of the former ruler to Petersburg, where it was buried with great solemnity in the Annunciation Church of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra. The birth of princes Peter and Alexei was hidden from the people; the cause of Anna's death was declared a "fireworm". After the death of his wife, Anton-Ulrich lived in Kholmogory for another 29 years. Former Emperor John Antonovich in 1756 was transported from Kholmogor to the Shlisselburg Fortress, where he died during an attempt to release him (July 5, 1764). The remaining children of Anna Leopoldovna, painful and epileptic, spent more than 36 years in exile. In 1779, after a trip to Kholmogory A.P. Melgunova, Empress Catherine entered into negotiations on a Braunschweig family with a Danish court (the Danish Queen Juliana Maria was the sister of Prince Anton) and in 1780 ordered the descendants of the former ruler to be sent to Gorsens, giving them 200,000 rubles. They went by sea from the Novo-Dvinsk fortress and, after a three-month journey, arrived in Gorsens. The Empress gave out 32 thousand annually for their maintenance, 8 thousand for each. Princes and princesses were Orthodox; clergy and servants arrived from Russia with them. On October 20, 1782, Princess Elizabeth died, on October 22, 1787, Prince Alexei died, and on January 30, 1798, Peter. There was a lonely deaf and tongue-tied, who could only speak Russian, Princess Catherine. In vain did she ask (1803) Emperor Alexander I for permission to return to Russia and end her life as a nun. She died in Gorsens on April 9, 1807 and was buried there along with her sister and brothers.

Russian Biographical Dictionary / www.rulex.ru / "The internal life of the Russian state from October 17, 1740 to November 25, 1741" (2 parts, Moscow, 1880 and 1886); Soloviev, "History of Russia", t. 21; "Collections of the Imperial Russian Historical Society", vol. 76, 80, 85, 86, 96; A. Bruckner, "Die Familie Braunschweig in Russland" (St. Petersburg, 1874); A. Brikner, "Emperor John Antonovich and his relatives" (bibliography until 1874; M., 1875); Russian Bulletin, 1874, No. 10 - 11; "Russian Biographical Dictionary", vol. II (St. Petersburg, 1900). V. Fursenko.

After the death of Peter II, Anna Ioannovna, the Dowager Duchess of Courland, was invited to the empty Russian throne. By the time of her accession to the throne, Anna Ioannovna was almost 37 years old; her age was no longer suitable for childbearing; the matter was further complicated by the fact that the empress had a long-standing cordial friend - Ernst Johann Biron, whose origin did not allow him to pretend to be the father of a prince or princess.

Subtle Chancellor Andrei Ivanovich Osterman and Shtalmeister Karl Gustav Levenvolde proposed a cunning solution to the succession problem, a troubled empress.

Portrait of Princess Catherine Ioannovna

In 1731, Anna Ioannovna announced the heir to the throne of the unborn child of her niece - Princess Mecklenburg-Schwerin Elizabeth Catherine Christina and, despite the unusual situation, all subjects were sworn in allegiance to the future heir. The princess was the daughter of the eldest sister of Anna Ioannovna - Princess Catherine and the Duke of Karl-Leopold of Mecklenburg-Schwerinsky.

Portrait of the Duke of Karl-Leopold of Mecklenburg-Schwerinsky

She was born on December 7, 1718 in the city of Rostock, and by the time of the oath she was not even married, because she was not yet thirteen years old; and nine of them, she spent in Russia. Of course, the choice of the groom became a very serious issue in this situation.

Of the two candidates, or rather, of the two alliances - with Prussia or Austria, preference was given to Austria.

In February 1731, Prince Anton-Ulrich of Braunschweig-Bevern-Luneburg was invited to Russia.

He was the son of the reigning Duke of Braunschweig, Friedrich Albert and Antoinette Amalia Braunschweig-Wolfenbuttel. By mother, he was the nephew of the wife of the Austrian emperor Charles VI Elizabeth, and Sofia Charlotte, the wife of Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich.

Here is how Prince Lady Rondo, the wife of the English envoy at the Russian court, describes: “The appearance of the prince is quite good, he is very blond, but looks pampered and rather constrained ... This, moreover, his stuttering makes it difficult to judge his abilities.”

Portrait of Anna Leopoldovna. Hood. I.G. Wedekind, 1732

Alas, according to Field Marshal Minich, "Prince Anton had the misfortune not to like the Empress, a very dissatisfied choice ... But a mistake was made, there was no way to correct him, without disappointing himself or others."

Without saying yes or no about the marriage, the empress left Anton-Ulrich in Russia, and granted him the rank of Colonel of the Cuirassier Regiment, hoping that over time everything would work out. However, the Princess of Mecklenburg, Anton-Ulrich did not like. All his attempts to get closer to his bride were unsuccessful.

“His zeal,” Biron subsequently wrote, “was rewarded with such coldness that for several years he could not flatter himself neither with the hope of love, nor with the possibility of marriage.” Disappointed Anton-Ulrich and the Empress's court. However, Princess Elizabeth was by no means a bright star in the court sky.

“She possesses neither beauty nor grace, and her mind has not yet shown any brilliant qualities. She is very serious, laconic and never laughs; it seems to me rather unnatural in such a young girl, and I think her seriousness is more likely to be stupid than judicious, ”from the letters of Lady Rondo.

The son of Field Marshal Minich, Ernst, spoke very differently about the princess: “She combined a noble and virtuous heart with great wit. Her actions were frank and sincere, and nothing was more unbearable for her than pretense and coercion, so necessary at court, why it happened that people, accustomed to rude caresses, unjustly considered her arrogant and supposedly despising everyone. Under the guise of external coldness, she was internally condescending and sincere. ... with the help of the foreigners around her, she knew the German language perfectly.

She understood French better than she spoke. Before reading books, she was a great hunter, she read a lot in both of these languages \u200b\u200band had an excellent taste for dramatic poem. ... she was medium in stature, stately and full, her hair was dark in color, and the facial appearance, although not regularly more beautiful, was pleasant and noble. In hair cleaning, she never followed fashion, but her own invention, which for the most part was removed not to face. ”

Portrait of Prince Anton-Ulrich. Hood. I.G. Wedekind

On May 12, 1733, Princess Elizabeth Catherine Christina of Mecklenburg-Schwerinsky converted to Orthodoxy and received a new name - Anna (in honor of the aunt Empress, who became the godmother). Patronymic for the young princess was chosen by the middle name of the father - Leopoldovna.

So, Princess Elizabeth was replaced by Anna Leopoldovna. Under this name, she remained in the history of the Romanov dynasty.

(Just a month later, at the 41st year of her life, Anna's mother, Duchess Catherine, died. She was solemnly buried in the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in St. Petersburg.)

Two years later, it suddenly turned out that Anna Leopoldovna had a passionate romance with the Polish-Saxon envoy, Count Linar. Moreover, secret meetings were helped by the teacher of the princess, Mrs. Aderkas.

The count was immediately recalled to Poland, and Madame Aderkas was expelled from Russia.

On the orders of the empress, Anna Leopoldovna was placed under severe control, the girl was almost completely isolated: “apart from solemn days, no one outsider dared to go in and strictly looked after all her actions.” These circumstances only strengthened her "... a taste for solitude, which she always dressed up with displeasure when she was to receive and appear in public."

Anna was especially tormented by her stay in society, and even people she knew well, not to mention court balls, receptions and other ceremonies. On the contrary, “the most pleasant hours for her were those that she spent in seclusion and in the most select small conversation, and there she was, how much she was free to do, she was so much fun to handle.”

Among other things: “She was by nature sloppy, tied her head with a white scarf, going to the mass of the day, didn’t wear her clothes and appeared in this form publicly at the table and in the afternoon playing cards with her chosen partners ...”.

Portrait of Anna Leopoldovna

By that time, Prince Anton-Ulrich had shown himself to be the best in military service and had distinguished himself especially in 1737, at the battle of Ochakov, having received the rank of general and two orders - Andrew the First-Called and Alexander Nevsky. True, military valor did not at all affect Anna Leopoldovna's attitude towards him - it was still hostile.

In 1738, Biron tried to take advantage of this, proposing to Princess Anna as the possible bridegroom of her son Peter. Moreover, the favorite of the empress was not even embarrassed by the age difference - Peter was six years younger than Anna.

“... he went to visit her and said that he had come to inform her on behalf of Her Majesty that she should marry with the right to choose between Prince of Brunswick and Prince of Courland. She said that she should always obey the orders of Her Majesty, but in the present case, she admitted, she would do so reluctantly, for she would rather die than marry any of them. However, if she really needs to get married, then she chooses the Prince of Braunschweig. ”

Yes, Biron was cruelly mistaken: despite serious gaps in education, Anna was fully aware of the height of her origin and position, and made a choice in favor of the prince, who came from an ancient and noble family.

Empress Anna Ioannovna came to the same decision once, saying to Biron: “No one wants to think about the fact that I have a princess in my arms who must be given in marriage. Time passes, she is already in time. Of course, neither the princess nor the princess likes me; but the person of our condition does not always marry by inclination. ”

Portrait of Anton-Ulrich

On July 1, 1739, the official engagement ceremony of Anna Leopoldovna and Anton-Ulrich took place; and two days later the wedding is in the Church of Our Lady of Kazan.

And again, let's turn to the letters of Lady Rondo:

“... all these events were arranged in order to bring together two people who, it seems to me, wholeheartedly hate each other; at least, it is thought that this can be said with confidence with respect to the princess: she found it very clearly throughout the week of festivities and continues to show the prince complete contempt when she is not in front of the empress. ”

Nevertheless, the newlyweds completed their main task, as it seemed then, to be extremely successful. On August 12, 1740, thirteen months after the wedding, Anna Leopoldovna gave birth to a son, John Antonovich.

On October 5, 1740, Empress Anna became seriously ill. Due to poor health, she signed the Act, in which John Antonovich was declared the Grand Duke and heir to the Russian throne.

On October 16, the empress wrote a will in which Biron was appointed regent until the seventeenth birthday of John, and the next day died. Emperor Ivan VI Antonovich was only two months and five days old.

Portrait of Ivan VI Antonovich

The reign of Ernst Johann Biron did not last long. Field Marshal Burchard Christoph Minich became his main rival, having organized a conspiracy against the regent, in which Prince Anton-Ulrich also took part.

On the night of November 8–9, 1740, Biron was captured and taken to the Shlisselburg fortress, and then exiled to the town of Pelym, Tobolsk province. On November 9, the oath of guards regiments for fidelity to the “Blessed Empress, ruler of Grand Duchess Anna of all Russia” took place.

Portrait of Anna Leopoldovna

Unfortunately, Anna did not possess any qualities necessary for governing the state. Field Marshal Minich wrote that Anna "by nature ... was lazy and never appeared in the Cabinet. When I came in the morning with papers ... that required a resolution, she, feeling her inability, often said: “I would like my son to be at such an age that I could reign myself.”

Such a ruler was very convenient, first of all, for ministers who received almost unlimited power, since she was mainly occupied with her personal life. Having become, in essence, the autocratic empress, Anna Leopoldovna continued to live as she had before. She still despised her husband, and often did not let the unlucky spouse into her half.

And yet, in July 1741, Anna gave birth to a second child - Princess Catherine. After a while, she returned to Petersburg the subject of her ardent passion - Count Linard, and many saw him as the new Biron. To keep up appearances, the count was engaged to Anna's favorite maid of honor, Julia Mengden. The regent's affection for maid of honor was so great that they were suspected of feelings much more tender than simple friendship. Shortly after the engagement, Count Linar went to Dresden to retire at the Saxon court, thereby avoiding the fate of Biron.

Portrait of Anna Leopoldovna. Hood. L. Caravac

On November 25, 1741, the Grand Duchess and ruler was arrested along with the whole family, the guards of the Preobrazhensky regiment. The coup was made in favor of Tsarevna Elizaveta Petrovna. On November 28, the new empress issued a manifesto on the expulsion of the Braunschweig family abroad.

Initially, they were supposed to be transported to Riga, from there to Mitau, and then to Germany. However, soon Elizabeth decided that in the event of her departure from Russia, the family of the former emperor could become dangerous and they were transferred to Dinamuende - a fortress near Riga. The family lived there for more than a year and, in the same place, was born in 1743, the second daughter - Elizabeth.

In January 1744, the head of the security Saltykov was ordered to send them to the city of Ranenburg, Voronezh province.

In August 1744, the former emperor Ivan Antonovich was forever separated from his parents. According to a secret decree of the empress, he was to be sent to a new place of residence in a closed carriage, without showing anyone or letting him out into the street. For the final observance of the secret, the boy was even changed his name - from now on he was supposed to be called Gregory, thereby deposing the emperor was put on a par with the impostors of the Time of Troubles (the government of Boris Godunov declared False Dmitry I by Grigory Otrepyev). Ivan and his family were separately sent to Solovki.

In addition to her son, Anna Leopoldovna was also separated from Julia Mengden. According to a letter from the new security chief, Major Korf: “This news plunged them into extreme sadness, revealed by tears and screams. Despite this and the princess’s painful condition (pregnancy - [Rostislav]), they replied that they were ready to fulfill the will of the empress. ”

John VI Antonovich and Anna Leopoldovna. 1741 year

In March 1745, Elizabeth wrote to Corfu: “Ask Anna to whom her diamond things are handed out, of which many will not turn out [on hand]. And if she, Anna, begins to lock herself up and doesn’t give anyone any diamonds, then say that I will be forced to search (torture) Julia (Julia) and if she [is] sorry, then she will not allow torment ”.

Not a very nice touch to the portrait of Elizabeth.

The transfer of prisoners lasted more than two months. A painful journey was interrupted due to impassability, in the city of Kholmogory, above Arkhangelsk. Both the former emperor and his parents with the other children were settled in the empty house of the Kholmogory bishop, divided into two parts isolated from each other. Ivan did not even suspect that his family lives in the other half of the house.

There are many facts suggesting that Ivan Antonovich was a normal, agile boy. According to the instructions, the room prepared for Ivan should not have windows: so that the boy “did not jump out of the window because of his playfulness.” He also knew who he was and who his parents were. The fact that he calls himself emperor, reported one of the guards of Ivan in 1759; and Ivan himself mentioned that his parents and soldiers called him that during the visit of Emperor Peter III to Shlisselburg in 1762.

In 1748, Ivan fell ill with measles and smallpox. At the commandant’s request, a decree came from St. Petersburg to not allow a doctor, and only before death is the presence of a clergyman, preferably a monk, permitted. And yet, the prisoner survived.

In January 1756, he was taken from Kholmogor to the Shlisselburg Fortress, where he was killed eight years later in an unsuccessful attempt to free him. His parents never found out about the tragic fate of their firstborn. In March 1745, Anna Leopoldovna gave birth to a second son and fourth child - Prince Peter; February 27, 1746 was born the last son - Alex.

On March 9, 1746, Anna Leopoldovna died of postpartum fever at the age of 27 years and 3 months. In the official death notice, Anna was called the "Blessed Princess Anne of Braunschweig-Luneburg."

Her body was delivered to St. Petersburg and on March 21, 1746, a funeral was held in the Annunciation Monastery of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra. The former ruler of Russia has found eternal peace with her mother and grandmother.

Anton-Ulrich outlived his wife much. After the accession of Catherine II, he was invited to leave Russia, but without children. The prince refused. He died on May 4, 1776, at the age of 60.

The children of Anna Leopoldovna and Anton-Ulrich, despite life in captivity, without education (in 1750, Elizabeth’s decree was forbidden to Kholmogory forbidding them to learn to read and write), they grew up smart, kind and nice people, they learned to read and write.

Governor A.P. who visited them Melgunov wrote to Empress Catherine II about Catherine Antonovna that, despite her deafness (during the coup of 1741, the four-month-old princess was dropped to the floor, which caused her hearing loss) “it’s clear from her circumvention that she is timid, evasive, polite and bashful, quiet and cheerful disposition. Seeing that others in a conversation are laughing, although they don’t know the reason, they are laughing with them ... Like brothers, sisters, they live together amicably and, moreover, are not cruel and philanthropic. In the summer, they work in the garden, go for chickens and ducks and feed them, and in winter they run [and] on horses along the pond, read church books and play cards and drafts. Maidens, moreover, are sometimes engaged in sewing linen. ”

After the death of Anton-Ulrich, Princess Elizabeth became the head of the family. She told the governor that “when we were still very young, father asked for freedom, when our father went blind, and we left our young age, we asked for permission to drive, but we received no answer.

But in the current situation, there is nothing left for us to wish for, except to live here in solitude. We are happy with everything, we were born here, are used to this place and are old ”, only“ we ask Her Majesty to beg for mercy, so that we are allowed to leave the house for meadows for a walk, we heard that there are flowers there that are not in our garden "To let the wives of officers be friends with them - so boring without society. And the last request: “Corsets, bonnets and currents send us from St. Petersburg, but we don’t use them for the fact that neither we nor our girls know how to put them on and wear them. Do mercy, send such a person who would be able to dress us up. ”

At the end of the conversation with Melgunov, Elizabeth said that if they fulfill these requests, they will be happy with everything and will not ask for anything, “we don’t want anything more and are happy to stay in this position forever.” After the governor’s report, Catherine II agreed to release the Kholmogory prisoners to Denmark, to the sister of Anton-Ulrich, the Danish Queen Julian-Margarita. July 1, 1780, the children of Anna Leopoldovna left Russia forever. In August, they arrived in Denmark and were settled in the small town of Gorzens in Jutland. But freedom was hopelessly late.

The first in October 1782, Princess Elizabeth died. Five years later, in 1787, Prince Alexei died, and in 1798, Prince Peter. The eldest princess, Catherine, lived the longest, almost sixty-six years. In August 1803, Emperor Alexander I received a letter from the Princess of Braunschweig, Catherine Antonovna. She begged to take her to Russia, home: “I pay all day, and I don’t know why God sent me here and why I live for so long in the world, and I remember Kholmogor every day because I had paradise there, and here - hell. ”

Having never received an answer, the last daughter of Anton-Ulrich and Anna Leopoldovna died on April 9, 1807. The branch of the Romanov-Miloslavsky faded away forever.